Understanding how microglia change state to adapt to different areas of the brain

Thought leaderJeffrey Stogsdill, Ph.D.Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative BiologyHarvard UniversityIn this interview, News Medical speaks with Jeffrey Stogsdill, Ph.D., about his latest research examining how microglia change their state to adapt to different areas of the brain. Can you please introduce yourself and tell us about your research background and interests, as well as why you decided to conduct your latest study? At the time of publication, I was a postdoc in the laboratory of Dr. Paola Arlotta in the Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology at Harvard University. I did my graduate work at Duke University with Dr. Cagla Eroglu made,…

Understanding how microglia change state to adapt to different areas of the brain

Can you please introduce yourself and tell us about your research background and interests, as well as why you decided to conduct your latest study?

At the time of publication, I was a postdoc in the laboratory of Dr. Paola Arlotta in the Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology at Harvard University. I did my graduate work at Duke University with Dr. Cagla Eroglu, where I gained my appreciation and fascination for the non-neuronal glial cells of the central nervous system, mainly astrocytes and microglia.

As a graduate student, I discovered that astrocyte cells associate tightly with neuronal synapses and even regulate how they wire together. I chose to do postdoctoral studies with Paola Arlotta because her lab was at the forefront of understanding how different neuronal cell types are assembled in the cerebral cortex. I felt there were major discoveries by combining my expertise in glial biology with the lab's expertise in neuronal diversity. Together, we discovered a communication code between excitatory neurons and microglia in the cerebral cortex, the region of the brain responsible for higher-order cognitive processes.

Researchers are increasingly learning about the many roles of microglia. What are these tiny immune cells and how do they play a role in brain function, health and disease?

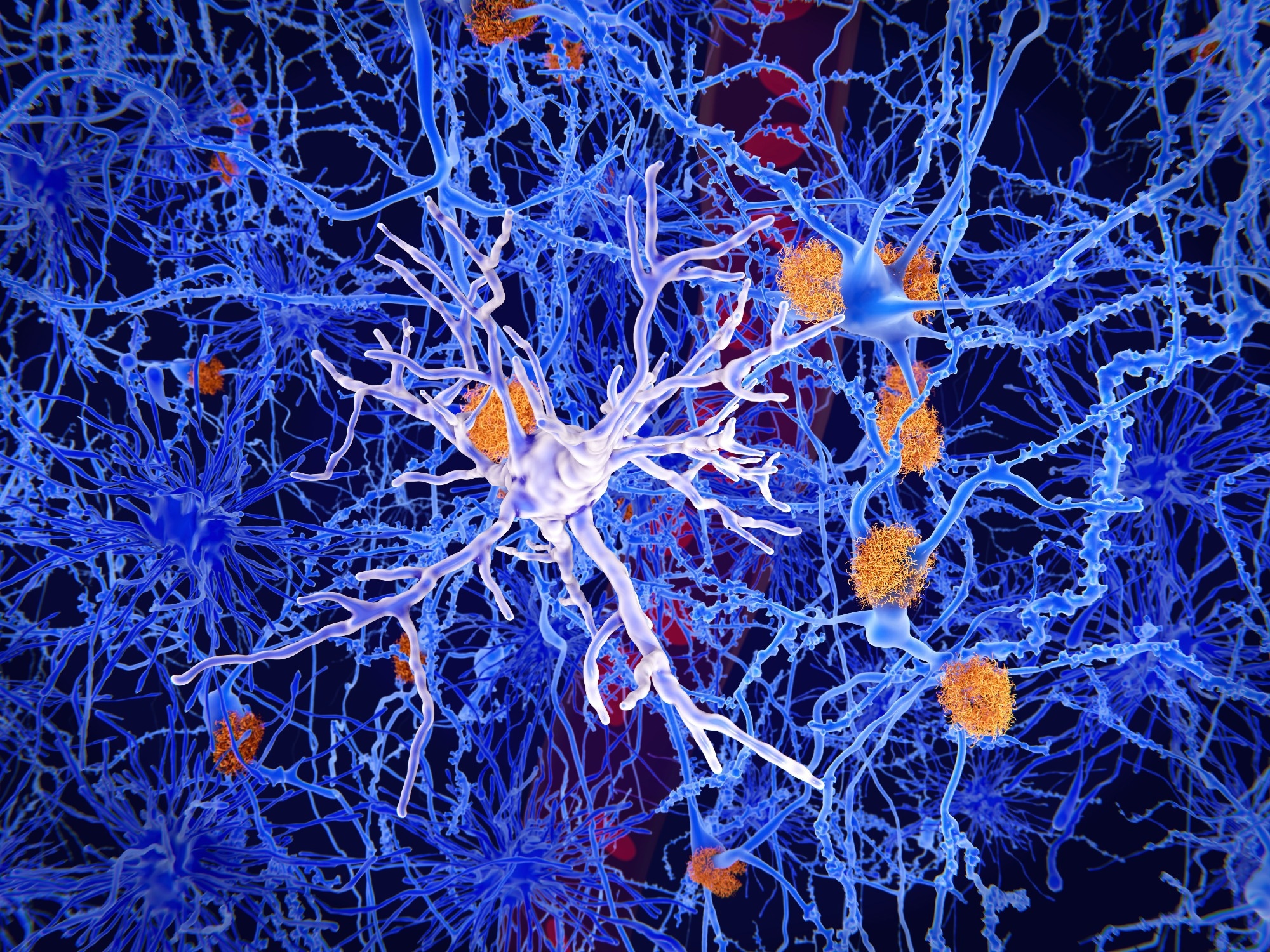

Microglia are the local macrophages of the brain, meaning they have an immunological cellular heritage. In fact, they originate from a region outside the developing embryo, called the yolk sac, where they travel through the bloodstream and colonize the brain, eventually remaining behind the largely cell-impermeable wall known as the blood-brain barrier.

In the past, microglia were known to function as cells that eat the brain and remove debris from the brain (i.e., dead cells and cleaning up after brain damage). However, we are now learning that they do so much more, including sensing and responding to neural activity. They also play an outsized role in human health. Many neurological diseases are either directly or indirectly linked to microglial function, including autism spectrum disorders, Alzheimer's disease, and multiple sclerosis, to name a few.

Their latest research suggests that microglia cells can “listen” to neighboring neurons and change their molecular state to match them. Can you explain what this means and how this happens?

By their immunological nature, microglia are cells that “listen” and “sense” the environment around them. They have many small branches that constantly scan their surroundings to, among other things, find weak synapses and areas of damage and assess the level of nearby neuronal activity. We knew from previous research that microglia from one brain region express different cell receptors (i.e., the molecules involved in hearing) than other brain regions, but it was unclear how this translated at the local level of an individual microglia.

We found that within a single brain region (the layers of the cerebral cortex), which houses many different types of excitatory neurons, they can locally control microglia in two important ways: 1) different neuron subtypes locally recruit different numbers of microglia to their area, and 2) they "tune" the transcription profiles of local microglia, much like a musician tuning an instrument to make the right sound. This last point is quite important because it suggests that different neurons involved in different brain activities adapt the cellular profile of local microglia to the needs of their circuits.

We postulate that this is carried out in part by different signaling molecules expressed by different classes of excitatory neurons. We found these by profiling the expression of all signaling molecules in neurons and correlating this expression atlas with all signaling molecules in different states (or tunes, back to the music analogy) of microglia. We were amazed to see the level of specificity in signaling between these major subdivisions of cells.

Their study was carried out using genetic profiling methods to examine the microglia in the different layers. Can you elaborate on how you conducted your research and what insights you gained?

We approached this question in two ways by profiling mouse microglia, which is a good, although not a perfect, correlate of the human brain. In the first approach, we removed the cortex and then carefully microdissected the layers of the cortex. We then extracted all microglia and profiled them using a powerful tool called single-cell RNA sequencing. This method allows researchers to view the RNA expression profile (in other words, the repertoire of expressed genes) of each individual cell in isolation from other cells.

Genetics & Genomics eBook

Compilation of the top interviews, articles and news from the last year.

Download a copy today

First, we found that all cells from all layers we extracted were microglia through the expression of genes unique and specific to microglia. But we then found that above the basal layer of identity there existed a secondary layer of gene expression that correlated with the layer from which the microglia were microdissected. This gave us the “gene signature” of each layer-enriched microglial state, or the matched state of microglia from each layer. It is important to note that each layer of the cortex houses a different subset of excitatory neurons. Thus, we were able to correlate neuron subtype (by layer) with microglial status (by layer).

The second approach used an even more powerful profiling tool that allowed us to look into the transcriptional expression of all cells (neurons, microglia, other glia, etc.) in the intact brain without having to microdissect it. This approach, called Multiplex Error-Robust Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (or MERFISH for short), was applied to the mouse brain using the gene signatures we found in our first profiling experiment described above. Using this method, we were able to map the exact location of each microglia and excitatory neuron in three dimensions with extraordinary precision.

With this map in hand, we found that microglial states exist in layers, as we had previously found. What was more exciting, however, was that each microglia resides in a neighborhood of unique neuron subtypes and that the state of the microglia depends on the local composition of their nearby neuron neighbors. This suggests that the level of specificity lies at the level of cellular interactions in neuron-microglia neighborhoods.

What are some of the consequences that occur when communication between microglia and their neuron partners goes wrong?

Our research did not address the effects of miscommunication between microglia and their neuronal partners. However, our signaling atlas provides the field with a wealth of starting points for identifying what might go wrong and, perhaps more importantly, how we might potentially repair or correct circuits when miscommunication occurs between neuronal subtypes and microglia.

A very interesting note from human research is that Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) disorders have been identified between neurons of the upper layer of the cortex and microglia. Our dataset is prepared to be mined to uncover the molecular mechanisms of these upper layer disorders in people with ASD.

How might the results of this new research help open the door to lines of research that can precisely target the communication between microglia and their neuron partners?

As I mentioned in the previous question, our signaling atlas between neuron subtypes and microglia is a treasure trove of data waiting to be mined by experts in the field of neuroimmunology. Many of the communication signals are pathways that can be “medicated” or altered through gene therapy. It is an exciting time to see how targeting microglia can repair neurons or neural circuits and ultimately perhaps neurological disorders.

What are the next steps for you and your research?

I moved to a biotechnology company that aims to use glial cells as a therapy for neurological diseases. I hope that the data generated from this published study will be a springboard for other laboratories to explore how to generate different microglial states in culture for testing, analysis, and therapy. I also hope that it can help provide new insights into mechanisms of neurological disease initiation or progression.

Where can readers find more information?

Readers can find the original study here:

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-05056-7

- https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-02005-2

About Jeffrey Stogsdill, Ph.D.

I am currently a senior scientist at Sana Biotechnology, trying to find ways to use glial cells as a therapy for neurological diseases. For the research on the paper discussed here, I worked as a postdoc in Paola Arlotta's laboratory in the Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology at Harvard University. Extensive bioinformatics analyzes were conducted by Kwanho Kim in the laboratory of Joshua Leven at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT. The project was conducted with funding from the NIH and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard (through Paola Arlotta and Joshua Levin) and with funding from HHMI (Jeff Stogsdill).

.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto