Link between shorter sleep later in life and several diseases

Human physiological processes rely heavily on sleep for their proper functioning. A recent PLOS Medicine journal study determined the association between sleep duration of older people aged 50, 60 and 70 and the incidence of multimorbidity. Significantly, the study used 25 years of follow-up data for analysis. Learning: Association between sleep duration at ages 50, 60 and 70 years and risk of multimorbidity in the UK: 25-year follow-up of the Whitehall II Cohort Study. Image credit: kudla / Shutterstock Lack of evidence regarding sleep duration and health status Although several studies have suggested a link between...

Link between shorter sleep later in life and several diseases

Human physiological processes rely heavily on sleep for their proper functioning. A recent one PLOS medicine A journal study determined the relationship between the sleep duration of older people aged 50, 60 and 70 and the frequency of multimorbidity. Significantly, the study used 25 years of follow-up data for analysis.

Lack of evidence regarding sleep duration and health status

Although several studies have suggested an association between sleep duration and the manifestation of chronic diseases (e.g., cancer and cardiovascular disease) and mortality, the nature of this association remains unclear.

When the same person has more than one chronic disease, it is called multimorbidity. However, there are not many studies on the connection between multimorbidity and sleep duration. Furthermore, it is not known whether sleep duration affects health, causes chronic diseases and subsequently leads to mortality.

Currently, 7 to 8 hours of sleep is recommended for older adults; However, future research should examine whether short or long sleep duration increases the risk of morbidity. The underlying biological mechanisms associated with short sleep and the occurrence of comorbidities are available; However, the influence of longer sleep on the manifestation of chronic diseases is not exactly clear.

Sleep patterns have been reported to change as a person ages. The question therefore arises as to whether changes in sleep behavior in middle or older age increase the risk of multimorbidity.

About the study

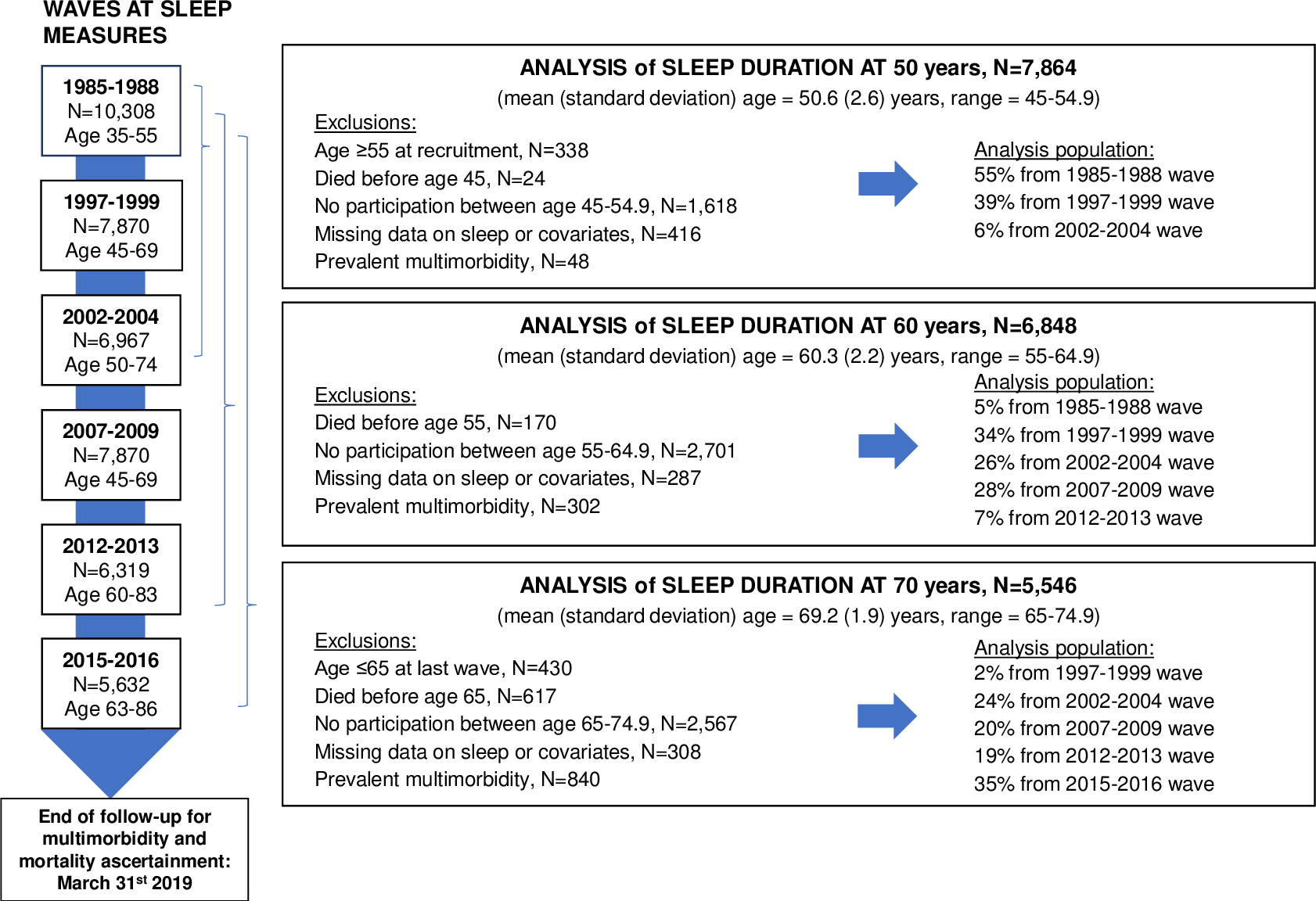

The current research used the Whitehall II cohort, an ongoing study from 1985 that included 10,308 (6,895 men and 3,413 women) British civil servants. As 99.9% of participants were linked to the UK National Health Service (NHS) electronic health records, relevant medical data were obtained from this service.

Self-reported information on participants' average sleep duration per week per night was collected in six data collection waves between 1985 and 2016. This information has been categorized by age, i.e. h. 50, 60 and 70 years. The Jenkins Sleep Problem Scale was used to assess sleep quality. Participants were asked about their sleep experiences, such as: B. Insomnia, difficulty sleeping, waking up several times during the night and difficulty falling asleep.

In this study, multimorbidity was defined as the presence of two or more chronic diseases out of thirteen identified chronic diseases based on clinical examinations in Whitehall up to March 2019.

Study results

A total of 7,864 participants without multimorbidity were aged 50 years. In this group, 4,446 developed the first chronic disease, 2,297 progressed to multimorbidity, and 787 subsequently died.

It was observed that those who slept less than five hours at age 50 had an increased risk of developing their first chronic disease compared to seven hours of sleep. Interestingly, sleeping longer than nine hours was not associated with such transitions.

The current prospective study presented three key findings. First, short sleep duration was consistently associated with an increased risk of multimorbidity. This observation applied to both middle-aged and older participants. Short sleep duration was also associated with initial disease onset and subsequent multimorbidity. However, it was not associated with mortality.

Second, long sleep duration was less likely at ages 60 and 70 and an incidence of multimorbidity was observed. However, this did not apply to participants who were 50 years old. Therefore, long sleep duration at age 50 was not associated with disease progression.

Third, accelerometer-based measurement of sleep duration in participants with a mean age of 69 years confirmed the association between sleep duration and the incidence of multimorbidity at ages 60 and 70 years.

Strengths and limitations

The major strengths of this study include the long follow-up period and the repeated measurement of sleep duration across different age groups. Furthermore, the use of multistate models provided more insight into the relationship between sleep duration and disease progression.

A fundamental limitation of this study is the small number of participants in the long sleep duration category. As a result, the authors were unable to draw conclusions about the frequency of multimorbidity in this group. Additionally, the self-report nature of the study increased the risk of biased results. The authors also pointed out the risk of reverse causality due to undiagnosed conditions in sleep measurements. The cohort included a limited number of non-white participants, so the results could not be generalized.

Conclusions

The current study clearly demonstrated the connection between short sleep duration and the development of multimorbidity. This observation applies to individuals in middle or late life. Short sleep duration at age 50 was associated with a higher risk of first chronic disease onset and subsequent multimorbidity. The current study recommended good sleep duration and quality for better health outcomes.

Reference:

- Sabia, S. et al. (2022) Zusammenhang zwischen der Schlafdauer im Alter von 50, 60 und 70 Jahren und dem Risiko einer Multimorbidität im Vereinigten Königreich: 25-Jahres-Follow-up der Whitehall-II-Kohortenstudie. PLOS Medicine, 19(10): e1004109. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004109, https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1004109

.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto