Delta waves may be useful for diagnosing concussions in younger patients

Measuring levels of a specific brain wave could lead to more objective, definitive methods of diagnosing concussions and determining when young athletes can safely return to play, according to a UT Southwestern study. Research shows that delta waves - which decrease with age and typically only appear in adulthood with illness or head injury - increased in high school football players with concussions. For most patients, these levels only decreased after symptoms subsided, according to the study published in Brain and Behavior. Since these waves are expected to fade as teenagers age, the results suggest that the delta peak...

Delta waves may be useful for diagnosing concussions in younger patients

Measuring levels of a specific brain wave could lead to more objective, definitive methods of diagnosing concussions and determining when young athletes can safely return to play, according to a UT Southwestern study.

Research shows that delta waves - which decrease with age and typically only appear in adulthood with illness or head injury - increased in high school football players with concussions. For most patients, these levels only decreased after symptoms subsided, according to the study published in Brain and Behavior.

Because these waves are expected to fade as teenagers age, the results suggest that the delta peak could be a marker not only for detecting concussion but also for measuring recovery in young athletes. We are one step closer to providing a clinical service that better informs patients about return-to-play decisions.”

Elizabeth Davenport, Ph.D., principal investigator, assistant professor of radiology, neurology and the Advanced Imaging Research Center at UT Southwestern

Concussions occur when a bump, blow, or jolt to the head causes the head and brain to move back and forth, causing chemical changes in the brain and sometimes stretching or damaging brain cells. Football is associated with the highest number of concussions of any sport played in the United States. These mild but traumatic brain injuries can cause debilitating symptoms such as headaches, vomiting, and vision problems, as well as long-term cognitive problems such as confusion, poor concentration, or memory loss.

Dr. However, Davenport explained that diagnosing concussions can be difficult. The neuropsychological tests and symptom checklists used for diagnosis can be subjective and non-specific, and studies have shown that up to 78% of gamblers hide their symptoms, increasing the risk of long-term harmful and even fatal consequences if they return to gambling before recovery.

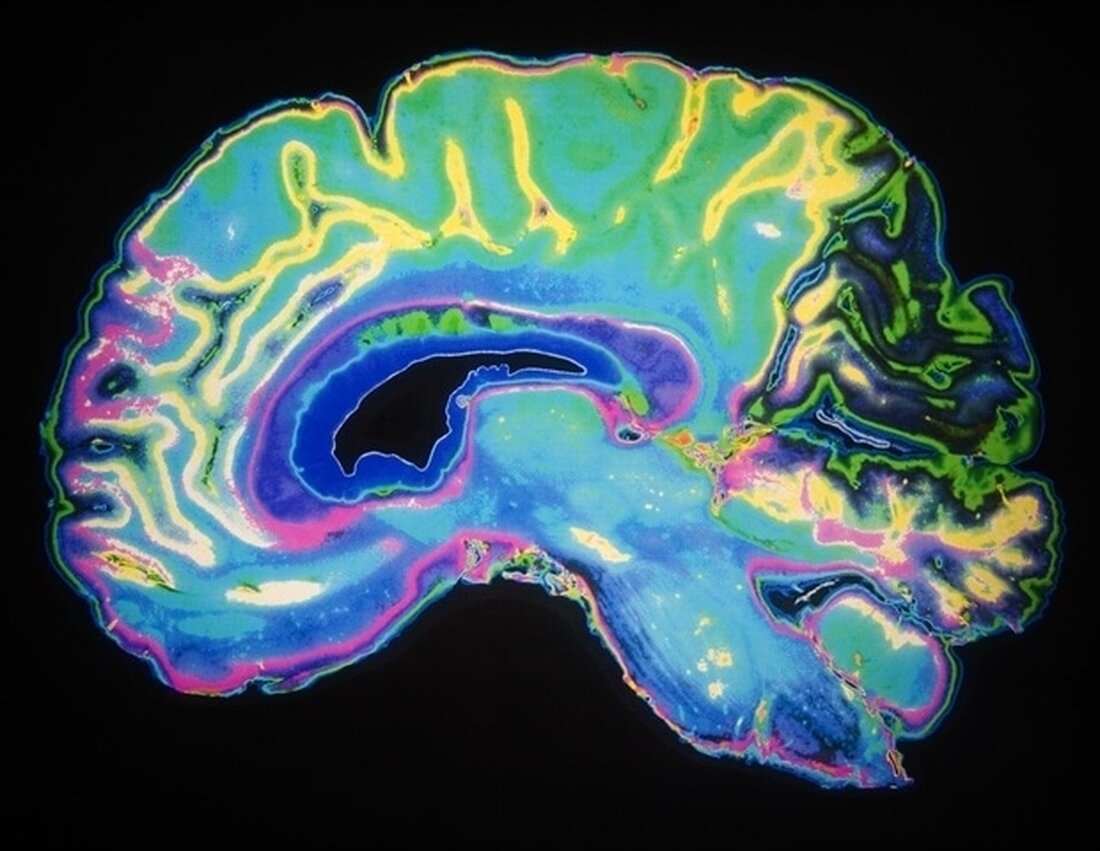

Studies using magnetoencephalography (MEG), a non-invasive type of brain mapping, have shown that adults who suffer concussions produce delta waves - a low-frequency brain activity not normally present in adulthood. But because children have active delta waves that fade before adulthood, it was unclear whether delta waves could be useful for diagnosing concussions in younger patients.

Breath Biopsy®: The Complete Manual eBook

Introduction to breath biopsy, including biomarkers, technology, applications, and case studies. Download a free copy

To answer this question, Dr. Davenport, along with colleagues from UT Southwestern and Wake Forest School of Medicine, three groups of eight high school athletes each: football players with concussions (including quarterback, cornerback, wide receiver, tight end, safety and leash positions); Soccer players matched for age, position, and demographic factors who had not sustained concussions; and athletes from non-contact sports, including swimming and tennis.

The volunteers received an MEG scan at Wake Forest Baptist Health before and after their season, as well as an additional scan if they were diagnosed with a concussion during the season. UTSW's analysis of the data collected showed that delta waves decreased slightly over the course of the season for non-contact athletes who had not experienced concussions, as expected during puberty. However, immediately after a concussion, delta waves increased significantly, which remained evident throughout the postseason.

Why this happens is not yet known. But, according to Dr. Davenport, Evidence from other studies suggests that an increase in delta waves is related to a naturally occurring metabolic cleansing mechanism, suggesting that this type of brain activity reflects a healing process. Regardless, she added, these results may eventually provide a way to diagnose concussions in young athletes and potentially show when healing is complete, which could help inform when these patients are ready to return to competition.

While those with a concussion had more delta waves on average, more studies are needed to determine the accuracy of using delta waves to diagnose individual adolescent cases, and further research will be necessary to bring this work into clinical practice, said Dr. Davenport. She and her team are planning an expanded study of concussed athletes using MEG in the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

Other UTSW researchers who contributed to this study include Jesse C. DeSimone, Ben Wagner and Joseph A. Maldjian.

Dr. Maldjian holds the Lee R. and Charlene B. Raymond Distinguished Chair in Brain Research.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01NS082453 and R01NS091602.

Source:

UT Southwestern Medical Center

Reference:

Davenport, EM, et al. (2022) MEG measured the increase in delta waves in adolescents after a concussion. Brain and behavior. doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2720.

.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto