What role do the origin, function and heterogeneity of macrophages play in health and disease?

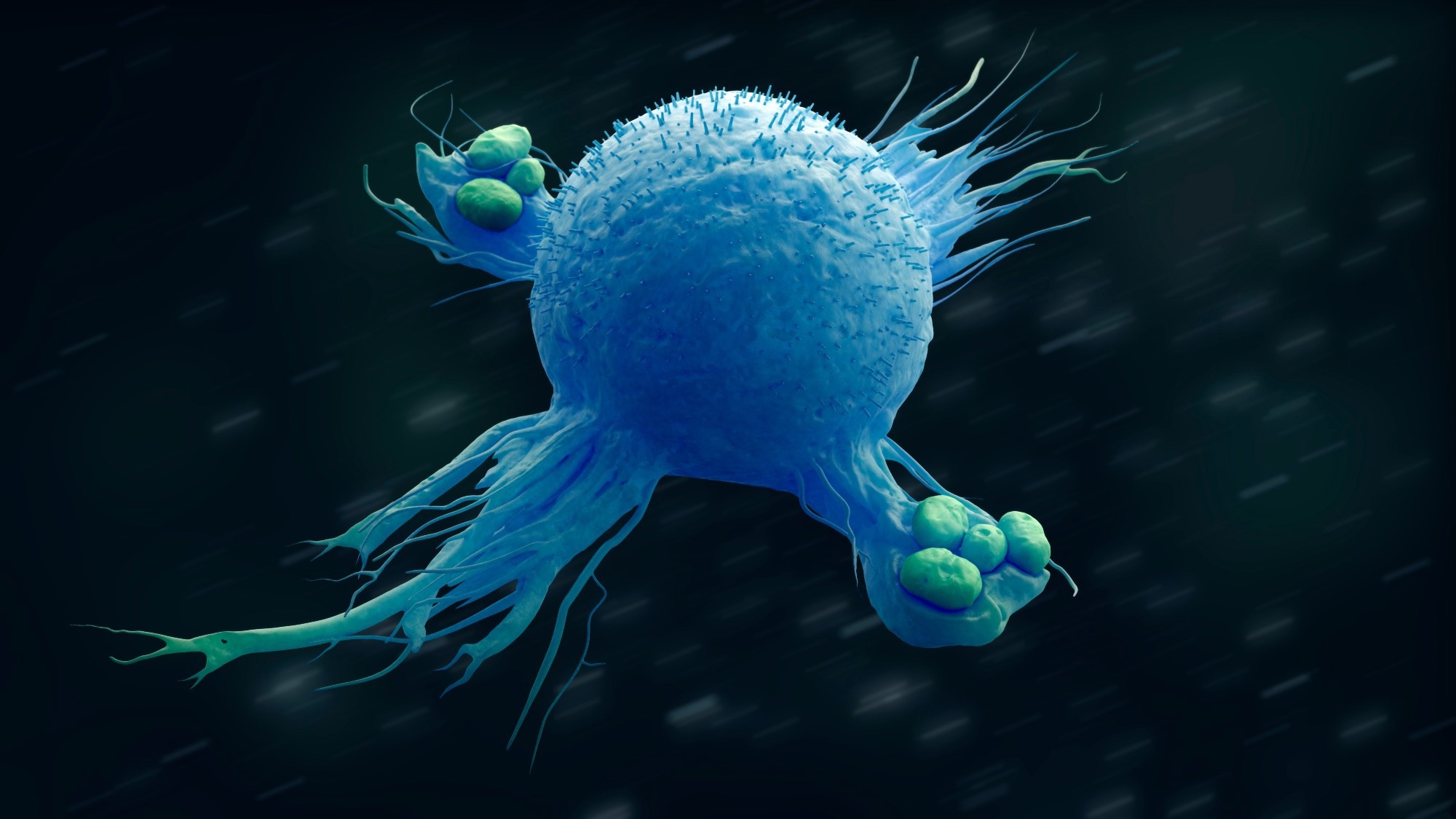

In a recent study published in Cell, researchers examined the wealth of information available on tissue macrophage heterogeneity. They pursued a conceptual framework for better understanding the origins and functions of diverse macrophages, focusing on the interplay between macrophage differentiation amid steady-state and disease-associated signals, time, and their contribution to homeostasis or disease progression. Learning: Macrophages in Health and Disease. Image source: urfin/Shutterstock Background Macrophages, tissue sentinel cells present in various organs throughout the body, clean their environment by phagocytosing cellular material and regulating tissue repair and maintenance. Monocyte-derived macrophages (mo-mac) and tissue-resident macrophages (RTMs), two subgroups...

What role do the origin, function and heterogeneity of macrophages play in health and disease?

In a recently published study in cell the researchers examined the wealth of information available on the heterogeneity of tissue macrophages. They pursued a conceptual framework for better understanding the origins and functions of diverse macrophages, focusing on the interplay between macrophage differentiation amid steady-state and disease-associated signals, time, and their contribution to homeostasis or disease progression.

Lernen: Makrophagen in Gesundheit und Krankheit. Bildquelle: urfin/Shutterstock

background

Macrophages, tissue sentinel cells present in various organs throughout the body, clean their environment by phagocytosing cellular material and regulating tissue repair and maintenance. However, monocyte-derived macrophages (mo-mac) and tissue-resident macrophages (RTMs), two subgroups of macrophages, differ during development, health, and disease.

Acquisition and application of the transcriptional programs that distinguish Mo-Macs from RTMs are critical to understanding when and where ontogeny (i.e., developmental origin) is important. All three factors play a role - the availability of cytokines, the balance of homeostatic cues and disease-associated signals, and biological time. Further research is needed to uncover the order of acquisition of these programs and how their induction might further diversify the differentiation trajectory of monocytes into RTMs at steady state and Mo-Macs during disease.

The study and its results

In the present study, researchers summarized the unique core functionalities of RTMs in different tissues, different types of RTMs and their tissue-specific activities. Furthermore, they illustrated how they differ from the functional contributions of Mo-Macs to disease progression. In fact, they observed that RTMs are gatekeepers of homeostasis.

In the hippocampus, kidney, and most commonly the bone marrow, liver, and spleen, macrophages and Kupffer cells (KC) monitor the start and end of the erythropoietic cycle, respectively. It is a classic example of how different RTMs clear cell nuclei and debris during development and subsequently eliminate other immune cells.

Protection of vital organs

Microglia, the major type of RTMs in the central nervous system (CNS), play a comprehensive role in managing neuronal health. For example, microglia join the neurovascular unit (NVU) to modulate blood flow and nutrient delivery to neurons and other glial cells. They also phagocytose dying nerve cells. More importantly, this relationship is not strictly unidirectional; Therefore, CNS and PNS neurons promote macrophage survival by producing growth factors such as interleukin-34 (IL-34).

Likewise, RTMs maintain vascular integrity. A classic example of this is how the RTMs in the human heart, called perivascular and cardiac macrophages, locally self-renew and work together to maintain cardiac function and vascular tone in peripheral tissues. They stimulate angiogenesis and proliferation of cardiomyocytes. Additionally, they maintain cardiac electrical conductivity and metabolic health by eliminating cardiac-derived exophers from junk mitochondria via phagocytic receptor tyrosine protein kinase (MerTK).

Skin and internal mucosal surfaces are most vulnerable to microbial invasion, and RTMs combat pathogens here. For example, alveolar macrophages migrating along the air-liquid-air interface of the lung capture and contain bacteria or virus-infected cells in the presence of pro-differentiation factors such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). They also prevent pathogenic and systemic inflammation without affecting the innate immune response to infection, thereby preventing unnecessary tissue destruction.

Monocyte-derived RTMs also protect tissue homeostasis. Remarkably, the brain maintains the native pool of embryonically derived RTMs throughout life. Even in the heart, pancreas, or intestine, the proportion of monocyte-derived RTMs increases over time. However, aging and changes in the microbiome reduce their self-renewal capacity and the ability to enter and colonize emerging niches. Therefore, circulating monocytes differentiate from the vasculature to form new RTMs and maintain niche integrity in a biological time-dependent manner.

Macrophage ontogeny is more than just a developmental origin

Cell ontogeny, embryonic or bone marrow derived, is more than a notation of developmental origin, age, or tissue type. Studies have characterized the molecular programs used by ontogenetically distinct macrophages and how they contribute to disease pathogenesis, but with much less precision.

The point at which homeostatic differentiation becomes unlikely and signals driving non-homeostatic differentiation begin to overwhelm macrophage niches may determine the degree to which specific disease-associated molecular programs of Mo-Macs are activated and influence disease progression. Indeed, it is crucial to investigate clues that make Mo-Macs pathogenic disease drivers in diseased tissues.

A number of disease-associated signals such as pro-inflammatory cytokines, alarmins, and damage-associated and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs and PAMPs) recruit excess inflammatory monocytes into tissues. During severe and chronic illness, RTMs cannot withstand continuous inflammation, leading to tissue barrier activation and death.

Conclusions

Exactly when recruited Mo-Macs help repopulate RTMs during disease recovery is unclear. However, the broader collection of these Mo-Macs in different tissues certainly shapes several disease states. Disease onset often results in the death of RTMs and circulating monocytes, creating vacant RTM niches. But unlike the macrophages that seed the tissue in its ontogeny, these Mo-Macs encounter a specific milieu and respond to inflammatory and disease-specific cues that distort their differentiation and prompt the expression of repertoires of molecular programs that further drive disease states. In fact, recruiting Mo-Macs comes at a high price.

These observations emphasize the importance of refining the use of macrophage ontogeny and developmental pathways, taking into account the kinetics of monocyte recruitment and differentiation and how this impacts their ability to revert to “unconventional” monocyte-derived RTMs after disease resolution. Most important is to develop an understanding of how niche-based formation of embryonic or monocyte-derived RTMs and their absence for Mo-Macs harboring disease-affected niches could be modulated to select for disease-resolving programs. Ultimately, it will be crucial to identify reliable markers that distinguish the subgroups of RTMs and the disease-related pool of Mo-Macs.

Identification of conserved Mo-Mac programs across disease states and multiple tissues could reveal candidate targets that could be ideal for therapeutic modulation. Examples include the Triggering Receptor Expressed On Myeloid Cells 2 (TREM2) program. In conclusion, further descriptive profiling and functional studies are needed to exploit the heterogeneity of macrophages in health and disease.

Reference:

- Matthew D. Park, Aymeric Silvin, Florent Ginhoux, Miriam Mera. (2022). Makrophagen in Gesundheit und Krankheit. Zelle. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.10.007 https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(22)01322-8#%20

.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto