Scientists shed light on the molecular events that underlie childhood movement disorder

Scientists from the UNC School of Medicine and the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, working with a team from Queen Mary University of London, have shed light on the molecular events underlying an inherited movement and neurodegenerative disorder known as ARSACS – autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay, named after two valleys in Quebec where the first cases were found. Children with ARSACS typically present with difficulty walking by the second year of life and a growing spectrum of neurological problems thereafter. In the cerebellum - an area of the brain that coordinates movement and balance - neurons called Purkinje cells die...

Scientists shed light on the molecular events that underlie childhood movement disorder

Scientists from the UNC School of Medicine and the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, working with a team from Queen Mary University of London, have shed light on the molecular events underlying an inherited movement and neurodegenerative disorder known as ARSACS – autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay, named after two valleys in Quebec where the first cases were found.

Children with ARSACS typically present with difficulty walking by the second year of life and a growing spectrum of neurological problems thereafter. In the cerebellum—an area of the brain that coordinates movement and balance—neurons called Purkinje cells die in people with ARSACS. Most patients are wheelchair-bound between the ages of 30 and 40 and have a shortened life expectancy, averaging in their mid-50s.

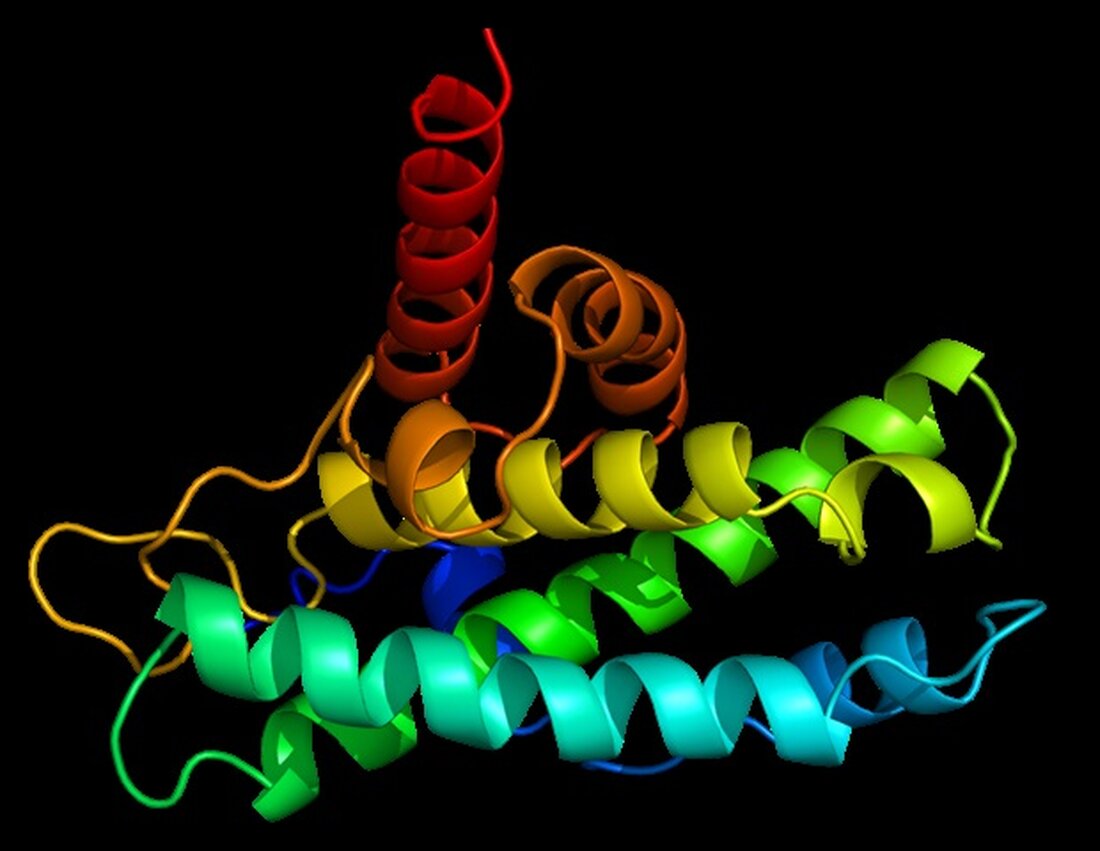

The disorder is caused by the mutation and loss of function of a gene called SACS, which encodes a very large protein called sacsin, which has been difficult to study directly in part because of its unwieldy size. Relatively little is known about its normal functions and how its absence leads to disease. But in a study published in Cell Reports, the collaborating researchers conducted the most comprehensive analysis of what happens in cells when sacsin is missing.

We tried to take an unbiased approach to understanding what goes wrong when cells lose sacsin. Our results suggest that Purkinje cell death in ARSACS may be due to changes in neuronal connectivity and synaptic structure.”

Justin Wolter, PhD, study co-senior author, postdoctoral fellow, UNC Neuroscience Center

The other co-author of the study was Dr. Paul Chapple, Professor of Molecular Cell Biology at Queen Mary University of London.

The study began with the Chapple lab and the UNC-Chapel Hill team working without each other's knowledge. “This project was started by Tammy Havener at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, then three postdoctoral fellows from different departments at UNC jumped on board – Wen Aw, Katherine Hixson and myself,” Wolter said. "When we realized that Lisa Romano in the Chapple lab had made similar discoveries using different approaches, we all decided to join forces and move forward together. I think this is a beautiful example of how open science and collaboration pay off for the community."

For this study, researchers used multiple -omics-based techniques in cultured human cells to examine how loss of sacsin alters protein levels and cellular organization. They confirmed the presence of defects identified in previous studies, such as abnormal aggregation of filament-forming structural proteins and defects in the number and dynamics of mitochondria, both of which are commonly observed in many neurodegenerative diseases.

Neuroscience eBook

Compilation of the top interviews, articles and news from the last year. Download a copy today

But they also found many anomalies that had not been previously identified. These included an overabundance of a protein called tau and altered dynamics of microtubules, which are intracellular transport pathways regulated by tau. The researchers found that the consequence of this altered transport was that many proteins did not get to the right place in the cell. Particularly affected were “synaptic adhesion proteins,” which help neurons form and maintain synapses — connections that neurons use to send signals to each other. Consistent with these observations, the team found changes in synaptic structure in the ARSACS mouse model. Importantly, these changes occur before the onset of neurodegeneration.

These discoveries expand the picture of how sacsin regulates multiple cellular processes. They also suggest the possibility that Purkinje cells - the neurons that appear to be most affected in ARSACS - could die because they lack connections to other neurons. Researchers will study these changes in the brain in more detail to understand whether this neurodegenerative disease is rooted in processes that occur during brain development.

Although ARSACS likely affects only a few thousand people worldwide, this type of research could have much broader implications, the researchers noted.

“There appears to be several overlaps between ARSACS and other brain diseases,” Chapple said. "For example, we have shown that there is a disruption in tau biology in cells lacking sacsin, and of course abnormalities in tau are also a known feature of Alzheimer's disease. Therefore, we believe that studying this rare neurological disease could provide insights into much more common diseases." “

“Much work remains to be done to understand the mechanisms by which synaptic connectivity is affected and whether it contributes to neuronal death,” Wolter said. “But if so, it could influence future therapeutic approaches.”

Source:

University of North Carolina Health Care

Reference:

Romano, LE Let al. (2022) Multi-omic profiling shows that the ataxia protein sacsin is required for integrin transport and synaptic organization. Cell Reports. doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111580.

.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto