Disposable coffee cups are already known to be an environmental nuisance because their thin plastic coating makes them extremely difficult to recycle.

Now a new study has found that hot drink containers release trillions of microscopic plastic particles into your drink.

Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology analyzed disposable hot beverage cups coated with low-density polyethylene (LDPE) — a soft, flexible plastic film often used as a waterproof liner.

They found that when these cups are exposed to water at 100°C (212°F), they release trillions of nanoparticles per liter into the water.

"The key takeaway here is that there are plastic particles everywhere we look. There are a lot of them. Trillions per liter," said NIST chemist Christopher Zangmeister.

"We don't know whether these have adverse health effects on people or animals. We just have a high level of confidence that they are there.'

Drinking coffee or tea from a paper cup is not only wasteful, but also risks swallowing thousands of microplastics, scientists warn

To analyze the nanoparticles released by coffee cups, Zangmeister and his team took the water in the cup, sprayed it into a fine mist, and allowed it to dry—isolating the nanoparticles from the rest of the solution.

This technique has previously been used to detect tiny particles in the atmosphere.

After the mist dried, the nanoparticles it contained were sorted by size and charge.

Researchers could then specify a specific size – for example nanoparticles around 100 nanometers – and feed them into a particle counter.

The nanoparticles were exposed to a hot vapor of butanol, a type of alcohol, and then quickly cooled.

As the alcohol condensed, the particles swelled from nanometers in size to micrometers, making them much more detectable.

This process is automated and is carried out by a computer program that counts the particles.

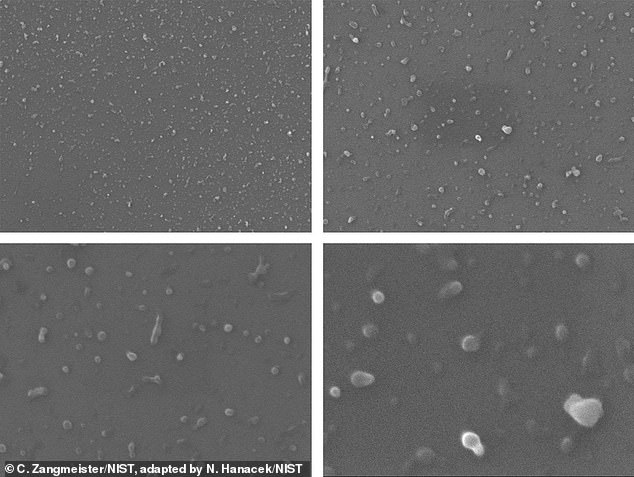

Researchers could also identify the chemical composition of the nanoparticles by placing them on a surface and observing them using a technique known as scanning electron microscopy.

High-resolution images of the nanoparticles found in disposable beverage cups such as coffee cups, at the micrometer level (one millionth of a meter).

This involves taking high-resolution images of a sample using a beam of high-energy electrons.

They also used Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, a technique that detects the infrared light spectrum of a gas, solid or liquid.

All of these techniques together provided a more complete picture of the size and composition of the nanoparticles.

In their analyzes and observations, the researchers found that the average size of the nanoparticles was between 30 nanometers and 80 nanometers, with a few over 200 nanometers.

“In the last decade, scientists have found plastics everywhere in the environment,” Zangmeister said.

“People have looked at snow in Antarctica, the bottom of glacial lakes, and found microplastics larger than about 100 nanometers, meaning they probably weren't small enough to enter a cell and cause physical problems.

“Our study is different because these nanoparticles are really small and are a big deal because they could enter a cell and potentially disrupt its function,” said Zangmeister, who also emphasized that no one has found this to be the case.

A similar study by the Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur in 2020 found that a takeaway hot drink in a disposable cup contained an average of 25,000 microplastics.

Metals such as zinc, lead and chromium were also found in the water. These, the researchers suggested, came from the same plastic lining.

The illustration shows a coffee cup with an enlarged section made of plastic particles. Disposable beverage cups like coffee cups can release trillions of nanoparticles, or tiny plastic particles, from the inner wall of the cup when the water is heated

In addition to coffee cups, NIST researchers also analyzed food-grade nylon bags such as baking liners - clear plastic sheets placed in baking pans to create a non-stick surface that prevents moisture loss.

They found that the concentration of nanoparticles released into hot water from food-grade nylon was seven times higher than that from the disposable beverage cups.

Zangmeister noted that there is no commonly used test to measure LDPE released into water from samples such as coffee cups, but there are tests for nylon plastics.

Findings from this study could aid efforts to develop such tests.

Microplastics enter waterways in various ways and end up suspended in the liquid. From the water they can be absorbed by seafood or absorbed by plants to get into our food

Zangmeister and his team have now analyzed other consumer goods and materials, such as fabrics, cotton-polyester, plastic bags and water stored in plastic pipes.

The findings from this study, combined with those from the other types of materials analyzed, will open up new avenues of research in this area in the future.

"Most studies on this topic aim to train colleagues. This paper will do both: train scientists and provide outreach," he said.

The study was published in the scientific journal Environmental Science and Technology.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto