The bacteria we breathe in every day

In a recent study published in the journal PNAS, researchers examined global airborne bacterial communities to understand their community structure and biogeographic distribution patterns. In addition, they examined their interactions with other Earth microbiomes, particularly surface habitats. Learning: Global airborne bacterial community - Interactions with Earth's microbiomes and anthropogenic activities. Image credit: Lightspring/Shutterstock Background The atmosphere is the most pristine microbial habitat on Earth, and airborne bacteria are the most complex and dynamic communities influencing Earth's microbiomes. There are more than 1 × 104 bacterial cells/m3 and hundreds of unique taxa in the air. Large-scale studies have...

The bacteria we breathe in every day

In a study recently published in the journal PNAS Researchers examined global airborne bacterial communities to understand their community structure and biogeographic distribution patterns. In addition, they examined their interactions with other Earth microbiomes, particularly surface habitats.

background

The atmosphere is the most pristine microbial habitat on Earth, and airborne bacteria are the most complex and dynamic communities influencing Earth's microbiomes. There are more than 1 × 104 bacterial cells/m3 and hundreds of unique taxa in the air. Large-scale studies have systematically documented the microbial characteristics in soils, oceans, and human waste. They have also suggested a correlation between airborne microbiomes and surface environments. However, there is a lack of studies documenting airborne microorganisms, particularly regarding their community structure.

Microbes do not live in isolation. Instead, they have multiple ecological relationships ranging from mutualism to competition. Therefore, determining their biogeographic distribution patterns and interactions with other Earth microbiomes that define their origin could shed light on the effects of climate/environmental change and anthropogenic activities.

About studying

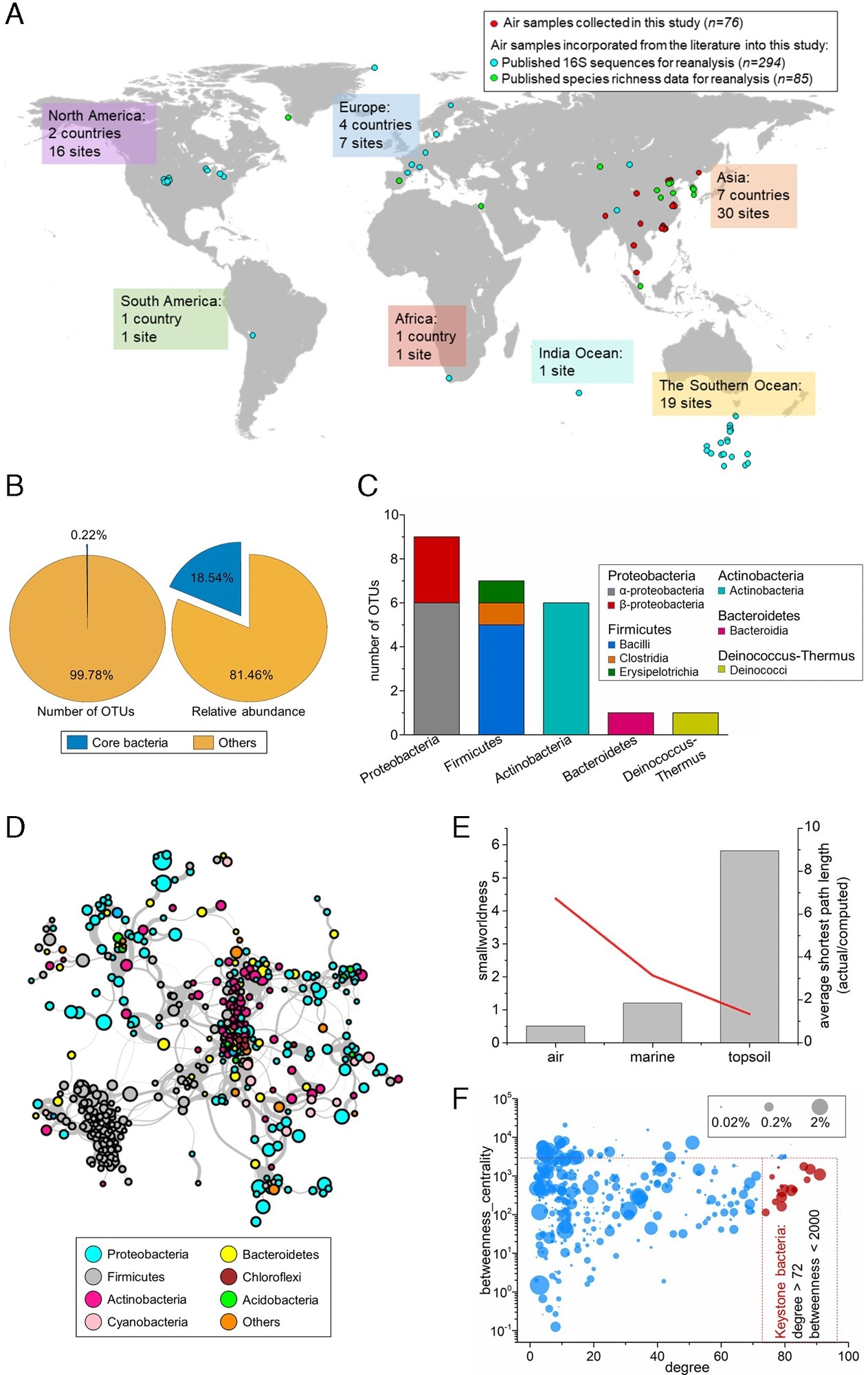

In the present study, researchers first developed a global data set on airborne bacteria to assess their degree of commonality and interrelationship. This dataset included 76 newly collected air particle samples combined with 294 samples collected for previous studies at 63 locations worldwide. Sampling sites varied in elevation and geography and included ground level, rooftops (from 1.5 m to 25 m in height) up to mountains 5,380 m above sea level, densely populated urban cities, and the remote Arctic Circle.

The team obtained the data set for comparison from the Earth Microbiome Project (EMP), which has collected more than 5,000 samples from 23 surface environments. The airborne bacterial reference catalog contained more than 27 million non-redundant 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequences.

In addition, researchers constructed a global airborne community co-occurrence network that included 5,038 significant correlation relationships (Spearman's ρ > 0.6) between 482 associated operational taxonomic units (OTUs). OTUs are analytical units grouped by DNA sequence similarity in microbial ecology. Finally, the team used structural equation modeling (SEM) to investigate the mechanisms that drive microbial communities. They also calculated the overall effect of environmental filters and bacterial interactions on community design.

Study results

10,897 taxa were detected from 370 individual air samples, and most bacterial sequences belonged to five phyla. Firmicutes, Alphaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes accounted for 24.8%, 19.7%, 18.4%, 18.1%, and 8.6% of these bacterial sequences, respectively. The abundance-occupancy relationship (AOR) between the samples occupied by a bacterial taxon and its average mass in the global air showed a sigmoid curve, similar to the observed pattern for the distribution of wildlife and plants on Earth.

Air is a free-flowing, dynamic ecosystem that enables long-distance transport of the bacterial communities it supports. However, its bacterial community appeared to be well connected to the local environment, particularly the source contributions and air quality conditions resulting from anthropogenic activities. Reduced filtering effects from the environment and increased human-related source contributions have led to lower biomass loads, higher frequencies of pathogenic bacteria, and more destabilized network structures.

Notably, airborne bacteria were not tightly connected compared to their counterparts in topsoil and marine environments and had an average intranode connectivity of 5.24. They had a random clustering approach, and the topology had low resistance to change. The observed distant relationships and loose clusters of the network suggested that the airborne bacterial community is more likely to be disrupted depending on the environmental conditions, which usually lead to drastic changes in bacterial composition. The functions of atmospheric bacterial taxa have been inferred based on their genetic information in other habitats.

Omics eBook

Compilation of the top interviews, articles and news from the last year. Download a free copy

The team found potential associations between airborne bacterial communities and other surface microbial habitats. The estimated total abundance of airborne bacteria (1.72 × 1024 cells) was comparable to that of the hydrosphere and one to three orders of magnitude lower than in other habitats (e.g., soil).

Of the 23 major Earth habitats examined in the current study, terrestrial air showed greater similarity to human and animal environments, while offshore air showed a closer relationship to oceanic systems. Furthermore, evaluations based on Bayesian methods showed that the characteristics of the corresponding surface environment determined the dominant sources of airborne bacteria. Notably, human sources contributed more to airborne bacteria in urban areas, particularly in land-based locations, a finding largely ignored in previous emissions modeling studies.

The authors found no significant differences in the richness of airborne bacterial communities between urban and natural areas within the same latitude range. However, geographical location played a role. The uniformity of the bacterial communities in city air was significantly lower. For example, the relative abundance of pathogenic species, Burkholderia and Pseudomonas, was higher in urban areas than in natural areas (5.56 and 2.50% versus 1.44 and 1.11%). In addition, bacteria contributed less to particulate matter (PM) mass in urban areas than in natural areas, suggesting that urbanization increased the proportion of non-biological particles in the air (e.g. dust).

The pathogens with the highest mortality risk, Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter species (ESKAPE), were more common in urban air. The co-occurrence network of urban airborne bacterial communities suggested that anthropogenic influences destabilized their network structure, which in turn also changed the bacterial taxonomic composition.

The authors found that several factors affected airborne bacterial communities - for example, geographical locations along with typical environmental factors. The biotic interactions between keystone and core bacterial communities and bacterial richness interacted significantly. Of all the deterministic processes, environmental filtering was the most important determinant of the structure and distribution of airborne microbial communities.

Conclusions

In summary, almost 46.3% of airborne bacteria originated from the environment, and stochastic processes primarily shaped community formation. Furthermore, the distinguishing feature of airborne bacteria in urban areas has been the increasing proportion of potential pathogens from human-related sources. Finally, airborne bacterial source profiles influenced a significantly higher percentage of structural variations than those for air quality and local meteorological conditions (43.7% versus 29.4% and 25.8%), as assessed by variational distribution analysis (VPA).

Reference:

- Globale luftgetragene Bakteriengemeinschaft – Wechselwirkungen mit den Mikrobiomen der Erde und anthropogenen Aktivitäten, Jue Zhao, Ling Jin, Dong Wu, Jia-wen Xie, Jun Li, Xue-wu Fu, Zhi-yuan Cong, Ping-qing Fu, Yang Zhang, Xiao- San Luo, Xin-bin Feng, Gan Zhang, James M. Tiedje, Xiang-dong Li, PNAS 2022, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2204465119, https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2204465119

.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto