Scientists say middle-aged people who can't balance on one leg are twice as likely to die early.

Researchers in Brazil who studied 2,000 people ages 50 to 75 found that those who couldn't stand on one leg for 10 seconds were 84 percent more likely to die within the next decade than those who completed the exercise.

The "simple and safe" balance test can detect people in poorer health - those who struggle to complete the activity are more likely to suffer from heart disease, high blood pressure and diabetes.

The "flamingo test" could be used in routine health checks for older adults to provide "useful information" about their risk of death, the team said.

Researchers in Brazil who studied 2,000 people ages 50 to 75 found that those who couldn't stand on one leg for 10 seconds were 84 percent more likely to die within the next decade than those who completed the exercise. The "flamingo test" could be used in routine health checks for older adults to provide "useful information" about their risk of death, the team said

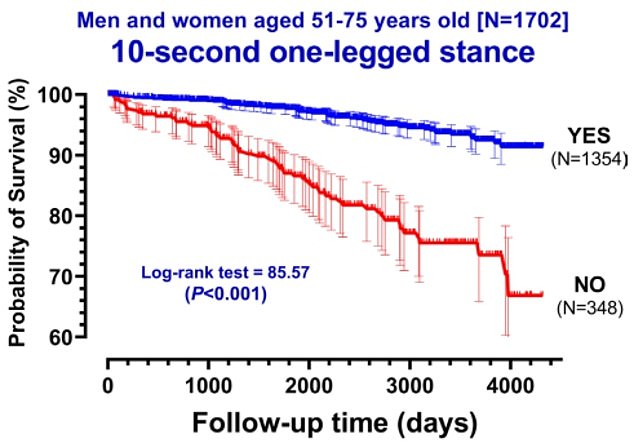

After controlling for age, gender and underlying health conditions, those who could not stand on one leg without support for 10 seconds were 84 percent more likely to die from any cause within the next decade. The graph shows the survival chances of those who completed the 10-second one-leg challenge (blue line) and those who failed (red line).

To ensure that all participants did this in the same way, they were asked to place the front of one foot on the back of the opposite lower leg while keeping their arms at their sides and looking straight ahead (pictured).

Improbable aerobic fitness, muscular strength and flexibility, balance is usually maintained fairly well until people are in their 60s - at which point it deteriorates.

Balance tests are not routinely included in health checks for older people, which the researchers say is due to the lack of a standardized test to measure them.

Aside from an increased likelihood of falls, there is also limited data on how balance relates to health.

To find out whether a balance test could be an indicator of health, the team at the exercise medicine clinic CLINIMEX in Rio de Janeiro examined the results of a previous study.

The study, which began in 1994, recruited 1,702 people in Brazil who underwent various fitness tests, including standing on one leg for 10 seconds without any support.

To ensure that all participants did this in the same way, they were asked to place the front of one foot on the back of the opposite lower leg while keeping their arms at their sides and looking straight ahead.

The researchers also collected data on weight, waist circumference and blood pressure. Volunteers were monitored for an average of seven years.

The results, published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine show that a fifth of participants were unable to stand on one leg.

The rate increased with age, with only five percent of 51- to 55-year-olds failing the task, compared to 54 percent of 71- to 75-year-olds.

About 123 people died during the course of the study.

The scientists found no clear trends in the cause of death between those who were able to complete the test and those who could not.

However, after controlling for age, gender and underlying health conditions, those who could not stand on one leg without support for 10 seconds were 84 percent more likely to die from any cause within the next decade.

Those who failed the test also tended to have poorer health. A higher proportion were obese, had heart disease, high blood pressure and unhealthy blood lipid levels.

And type 2 diabetes was three times as common in this group.

The researchers noted that all participants were white Brazilians, so the results may not apply to other ethnicities and nationalities.

And no information was available about factors that could affect the balance, such as: B. the volunteers' recent fall history, their physical activity level, diet, smoking and drug use.

However, the researchers noted that the 10-second balance test “provides the patient and healthcare professional with rapid and objective feedback regarding static balance.”

They said it “adds useful information about mortality risk in middle-aged and older men and women.”

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto