Characteristics of Cancer: New Dimensions

Preface The Hallmarks of Cancer Conceptualization is a heuristic tool for distilling the enormous complexity of cancer phenotypes and genotypes into a preliminary set of underlying principles. As knowledge of cancer mechanisms has advanced, other facets of the disease have emerged as potential refinements. This raises the prospect that phenotypic plasticity and disordered differentiation are a distinct characteristic ability, and that non-mutational epigenetic reprogramming and polymorphic microbiomes both represent characteristic enabling properties that facilitate the acquisition of characteristic abilities. Furthermore, senescent cells of different origins can be added to the list of functionally important cell types in the tumor microenvironment. Meaning Cancer is scary in...

Characteristics of Cancer: New Dimensions

Preface

The Hallmarks of Cancer Conceptualization is a heuristic tool for distilling the enormous complexity of cancer phenotypes and genotypes into a preliminary set of underlying principles. As knowledge of cancer mechanisms has advanced, other facets of the disease have emerged as potential refinements. This raises the prospect that phenotypic plasticity and disordered differentiation are a distinct characteristic ability, and that non-mutational epigenetic reprogramming and polymorphic microbiomes both represent characteristic enabling properties that facilitate the acquisition of characteristic abilities. Furthermore, senescent cells of different origins can be added to the list of functionally important cell types in the tumor microenvironment.

Meaning

Cancer is frightening in the breadth and scope of its diversity, which includes genetics, cell and tissue biology, pathology and response to therapy. Increasingly powerful experimental and computational tools and technologies are providing an avalanche of “big data” about the myriad disease manifestations that cancer encompasses. The integrative concept embodied in the hallmarks of cancer helps distill this complexity into an increasingly logical science, and the preliminary new dimensions presented in this perspective can add value to this endeavor to better understand the mechanisms of carcinogenesis and malignant progression and apply this knowledge to cancer medicine.

introduction

The Hallmarks of Cancer have been proposed as a set of functional capabilities that human cells acquire as they move from normality to neoplastic growth states, more specifically capabilities critical to their ability to form malignant tumors. In these articles ( 1, 2 ), Bob Weinberg and I listed what we envisioned as commonalities that unify all types of cancer cells at the level of cellular phenotype. The intent was to provide a conceptual framework that would allow the complex phenotypes of diverse human tumor types and variants to be rationalized in relation to a common set of underlying cellular parameters. Initially, we envisioned the complementary inclusion of six different brand capabilities and later expanded this number to eight.

This formulation was influenced by the recognition that human cancers develop as products of multistep processes and that the acquisition of these functional capabilities could be attributed in some way to the distinct steps of tumor pathogenesis. The diversity of malignant pathogenesis, encompassing multiple tumor types and an increasing plethora of subtypes, involves various aberrations (and thus acquired abilities and properties) that are the result of tissue-specific barriers that are necessarily bypassed during certain tumorigenesis pathways. Although we recognize that such specialized mechanisms may be helpful, we have limited the designation of the hallmarks to parameters that have a broad impact across the spectrum of human cancers.

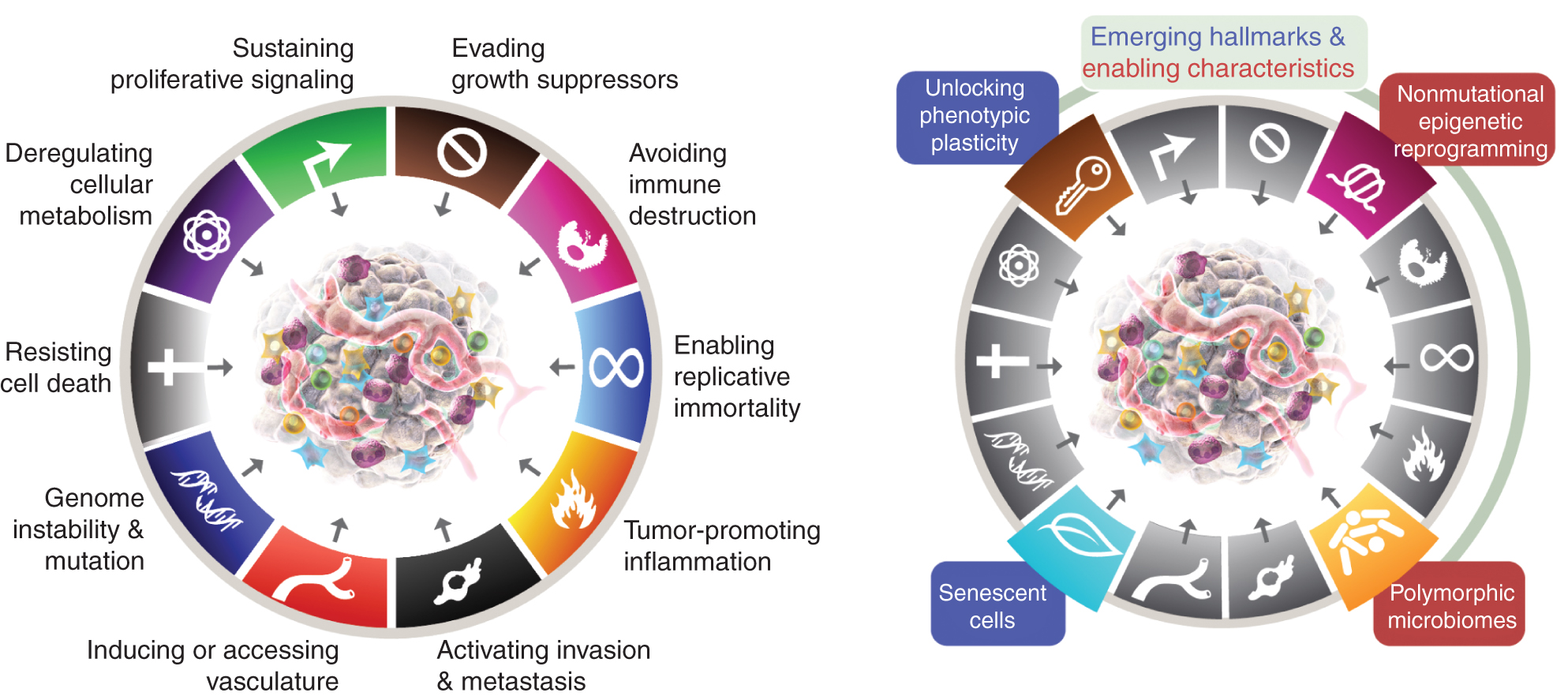

The eight hallmarks currently include (Fig.1, left) the acquired abilities to maintain proliferative signaling, avoid growth suppressors, resist cell death, enable replicative immortality, induce/access vessels, activate invasion and metastasis, reprogram cellular metabolism, and avoid destruction of the immune system. In the most recent elaboration of this concept (2), deregulation of cellular metabolism and avoidance of immune system destruction were demarcated as “emerging hallmarks,” but now, eleven years later, it is apparent that, similar to the original six, they can be considered core hallmarks of cancer and are included as such in the current narrative (Fig. 1, left).

Figure 1

The hallmarks of Cancer currently embody eight distinctive abilities and two supporting qualities. In addition to the six acquired capabilities - hallmarks of cancer - proposed in 2000 (1), the two preliminary "emergent hallmarks" introduced in 2011 (2) - cellular energetics (now more commonly referred to as "reprogramming of cellular metabolism") and "avoiding immune destruction" - have been sufficiently validated to be considered part of the core set.

Given the growing recognition that tumors can be adequately vascularized, either by switching on angiogenesis or by co-opting normal tissue vasculature ( 128 ), this hallmark is also more broadly defined as the ability to induce or otherwise access vasculature supporting tumor growth primarily through invasion and metastasis.

The 2011 sequel also included “tumor-promoting inflammation” as a second enabling trait, complementing the overarching “genome instability and mutation,” which together were fundamentally involved in activating the eight signature (functional) capabilities required for tumor growth and progression. True, this review includes additional proposed new hallmarks and enabling features, including “unlocking phenotypic plasticity,” “non-mutational epigenetic reprogramming,” “polymorphic microbiomes,” and “senescent cells.” The trademarks of the cancer graphic were adopted from Hanahan and Weinberg (2).

As we noted at the time, these distinctive features alone cannot address the complexity of cancer pathogenesis, i.e. h. the precise molecular and cellular mechanisms that allow the developing preneoplastic cells to develop and acquire these aberrant phenotypic abilities during the course of tumorigenesis and malignant progression.

Accordingly, we have added another concept to the discussion presented as “enabling features,” consequences of the aberrant state of the neoplasm that provide the means by which cancer cells and tumors can acquire these functional features. As such, the enabling properties are reflected in molecular and cellular mechanisms through which hallmarks are acquired, rather than in the above eight skills themselves. These two activation processes were genome instability and tumor-promoting inflammation.

We further recognized that the tumor microenvironment (TME), defined herein as composed of heterogeneous and interactive populations of cancer cells and cancer stem cells along with a variety of recruited stromal cell types—the transformed parenchyma and associated stroma—is now widely appreciated to play an essential role in tumorigenesis and malignant progression.

Given the ongoing interest in these formulations and our continued intention to encourage ongoing discussion and refinement of the Hallmarks schema, it is appropriate to consider a frequently asked question: Are there additional features of this conceptual model that could be incorporated, taking into account the need to ensure this? that they are broadly applicable across the spectrum of human cancers? Accordingly, I present several potential new hallmarks and enabling features that could, in due course, be integrated as core components of the hallmarks of cancer conceptualization.

These parameters are “unlocking phenotypic plasticity,” “non-mutational epigenetic reprogramming,” “polymorphic microbiomes,” and “senescent cells” (Fig. 1, Right). Importantly, the examples presented in support of these theses are illustrative but by no means comprehensive, as there is a growing and increasingly compelling body of published evidence to support each vignette.

Tapping phenotypic plasticity

During organogenesis, the development, determination, and organization of cells into tissues to perform homeostatic functions is accompanied by terminal differentiation, with progenitor cells ceasing to grow, sometimes irreversibly, as these processes culminate. As such, the end result of cellular differentiation is, in most cases, antiproliferative, forming a clear barrier to continued proliferation necessary for neoplasia.

There is increasing evidence that unlocking the normally limited capacity for phenotypic plasticity to circumvent or escape the state of terminal differentiation is a critical component of cancer pathogenesis ( 3 ). This plasticity can act in several manifestations (Fig. 2). Thus, nascent cancer cells that originate from a normal cell that has evolved along a path that approaches or assumes a fully differentiated state can reverse course by dedifferentiating back to progenitor-like cell states.

Conversely, neoplastic cells arising from a progenitor cell destined to follow a pathway leading to terminal differentiation can short-circuit the process and maintain the expanding cancer cells in a partially differentiated, progenitor-like state. Alternatively, transdifferentiation may occur in which cells originally committed to one differentiation pathway switch to a completely different developmental program and thereby acquire tissue-specific characteristics that were not predetermined by their normal cells of origin.

The following examples support the argument that different forms of cellular plasticity reveal phenotypic plasticity. On the left, phenotypic plasticity is arguably an acquired characteristic ability that enables various perturbations of cell differentiation, including (i) dedifferentiation from mature to progenitor states, (ii) stalled (terminal) differentiation from progenitor cell states, and (iii) transdifferentiation into other cell lineages. Three prominent modes of impaired differentiation that are integral to cancer pathogenesis are shown on the right.

By differentially perverting the normal differentiation of progenitor cells into mature cells in developmental lineages, tumorigenesis and malignant progression arising from cells of origin in such pathways are facilitated. The trademarks of the cancer graphic were adopted from Hanahan and Weinberg (2).

Figure 2

Dedifferentiation

Colon carcinogenesis is an example of impaired differentiation, as there is a teleological need for incipient cancer cells to escape the conveyor belt of terminal differentiation and exfoliation, which could in principle occur through dedifferentiation of colon epithelial cells that have not yet terminally differentiated or through stalled differentiation of progenitor/stem cells in the crypts that give rise to these differentiating cells. Both differentiated cells and stem cells have been implicated as cells of origin for colon cancer ( 4 – 6 ).

Two developmental transcription factors (TF), the homeobox protein HOXA5 and SMAD4, the latter involved in BMP signaling, are highly expressed in differentiating colon epithelial cells and are typically lost in advanced colon carcinomas, which characteristically express markers of stem and progenitor cells. Functional perturbations in mouse models have shown that forced expression of HOXA5 in colon cancer cells restores differentiation markers, suppresses stem cell phenotypes, and impairs invasion and metastasis, providing a rationale for its characteristic downregulation ( 7 , 8 ).

In contrast, SMAD4 enforces both differentiation and suppression of proliferation driven by oncogenic WNT signaling, which is revealed by the engineered loss of SMAD4 expression, providing an explanation for its loss of expression to allow dedifferentiation and subsequently WNT-driven hyperproliferation ( 5 ).

Notably, the loss of these two “differentiation suppressors” with the resulting dedifferentiation is associated with the acquisition of other hallmark abilities, as well as other hallmark-inducing regulators, complicating the strict definition of this provisional hallmark as separable and independent.

Another line of evidence concerns the suppressed expression of the MITF master regulator of melanocyte differentiation, which appears to be involved in the genesis of aggressive forms of malignant melanoma. Loss of this developmental TF is associated with reactivation of neural crest progenitor genes and downregulation of genes that characterize fully differentiated melanocytes. The reappearance of the neural crest genes indicates that these cells return to the progenitor state from which melanocytes arise developmentally.

Furthermore, a lineage tracing study of BRAF -induced melanomas established mature pigmented melanocytes as cells of origin that undergo dedifferentiation during the course of tumorigenesis ( 9 ). Notably, the mutant BRAF oncogene, found in more than half of cutaneous melanomas, induces hyperproliferation, which precedes and can therefore be mechanistically separated from the subsequent dedifferentiation that arises from downregulation of MITF.

Another study functionally implicated the upregulation of the developmental TF ATF2, whose characteristic expression in mouse and human melanomas indirectly suppresses MITF1, concomitant with malignant progression of the consequently dedifferentiated melanoma cells ( 10 ). Conversely, expression in melanomas of mutant forms of ATF2 that cannot suppress MITF results in well-differentiated melanomas ( 11 ).

Furthermore, a recent study ( 12 ) has linked lineage dedifferentiation to malignant progression of pancreatic islet cell neoplasms to metastasis-prone carcinomas; these neuroendocrine cells and derived tumors arise from a developmental lineage distinct from that which generates the far greater number of neighboring cells that form the exocrine and pancreas and the resulting ductal adenocarcinomas.

Remarkably, the multistep differentiation pathway from islet progenitor cells to mature β-cells has been thoroughly characterized ( 13 ). Comparative transcriptome profiling shows that adenoma-like islet tumors are most similar to immature but differentiated insulin-producing β-cells, while the invasive carcinomas are most similar to embryonic islet cell precursors. Progression to poorly differentiated carcinomas involves an initial step of dedifferentiation, which initially does not involve increased proliferation or reduced apoptosis compared to well-differentiated adenomas, both of which tend to occur later.

Thus, the discrete step of dedifferentiation is not driven by observable changes in the characteristic features of sustained proliferation and resistance to apoptosis. Rather, the upregulation of a miRNA previously implicated in specifying the islet progenitor state is one that is downregulated during terminal differentiation of β-cells, 12).

Blocked differentiation

While the above examples illustrate how suppression of differentiation factor expression can facilitate tumorigenesis by allowing better differentiated cells to dedifferentiate into progenitors, in other cases incompletely differentiated progenitor cells may suffer regulatory changes that actively block their further progression into fully differentiated, typically non-proliferative states.

It has long been documented that acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) results from a chromosomal translocation that fuses the PML locus to the gene encoding the retinoic acid α nuclear receptor (RARα). Myeloid progenitor cells carrying such translocations are apparently unable to continue their usual terminal differentiation into granulocytes, resulting in cells trapped in a proliferative, promyelocyte-like progenitor stage ( 14 ).

Proof of concept for this scheme comes from the treatment of cultured APL cells, mouse models of the disease, and affected patients with retinoic acid, the ligand of RARα; This therapeutic treatment causes the neoplastic APL cells to differentiate into apparently mature, nonproliferating granulocytes, thereby short-circuiting their progressive proliferative expansion (14–16).

A variation on this theme concerns another form of acute myeloid leukemia, this one carrying the t(8;21) translocation that produces the AML1-ETO fusion protein. This protein alone can transform myeloid progenitors, at least in part by blocking their differentiation. Therapeutic intervention in mouse models and patients with a pharmacological inhibitor of a chromatin-modifying histone deacetylase (HDAC) causes myeloid leukemia cells to resume differentiation into cells with a more mature myeloid cell morphology. Accompanying this reaction is a reduction in proliferative capacity, thereby impairing the progression of this leukemia ( 17, 18 ).

A third example in melanoma involves a developmental TF, SOX10, which is normally downregulated during melanocyte differentiation. Gain and loss of function studies in a zebrafish model of BRAF -induced melanomas have shown that abnormally maintained expression of SOX10 blocks the differentiation of neural progenitor cells into melanocytes, allowing the formation of BRAF -driven melanomas ( 19 ).

Other examples of differentiation modulators include the metabolite alpha-ketoglutarate (αKG), a necessary cofactor for a number of chromatin-modifying enzymes that has been shown to be involved in stimulating certain differentiated cell states. In pancreatic cancer, the tumor suppressor p53 stimulates the production of αKG and the maintenance of a more differentiated cell state, while a prototypical loss of p53 function leads to a reduction in αKG levels and consequent dedifferentiation, which is associated with malignant progression ( 20 ).

In one form of liver cancer, mutation of an isocitrate dehydrogenase gene (IDH1/2) does not result in the production of differentiation-inducing αKG, but rather a related “oncometabolite,” D-2-hydroxygluterate (D2HG), which has been shown to block hepatocyte differentiation of liver progenitor cells through D2HG-mediated repression of a master regulator of hepatocyte differentiation and quiescence, HNF4a.

D2HG-mediated suppression of HNF4a function triggers a proliferative expansion of hepatocyte progenitor cells in the liver, which become susceptible to oncogenic transformation upon subsequent mutational activation of the KRAS oncogene, which drives malignant progression to cholangiocarcinoma of the liver ( 21 ). The IDH1/2 mutant and its oncometabolite D2HG also function in a variety of myeloid and other solid tumor types, where D2HG inhibits αKG-dependent dioxygenases required for histone and DNA methylation events that mediate changes in chromatin structure during developmental lineage differentiation, thereby freezing the onset of cancer cells in a progenitor state (22, 23).

An additional, related concept is “bypassed differentiation,” in which partially or undifferentiated progenitor/stem cells exit the cell cycle and lie dormant in protective niches, with the potential to reinitiate proliferative expansion ( 24 ), although still with the selective pressure to disrupt their programmed differentiation in one way or another.

Transdifferentiation

The concept of transdifferentiation has long been recognized by pathologists in the form of tissue metaplasia, in which cells of a particular differentiated phenotype markedly change their morphology to become clearly recognizable as elements of another tissue, a prominent example of which is Barrett's esophagus, where chronic inflammation of the stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus induces transdifferentiation into a simple columnar epithelium characteristic of the intestine, thereby facilitating the subsequent development of adenocarcinomas rather than the squamous cell carcinomas expected from this squamous epithelium (3).

Now, molecular determinants are revealing mechanisms of transdifferentiation in various cancers, both for cases where gross tissue metaplasia is obvious and others where it is somewhat more subtle, as the following examples illustrate.

An informative case for transdifferentiation as a discrete event in tumorigenesis concerns pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), in which one of the involved cells of origin, the pancreatic acinar cell, can transdifferentiate into a ductal cell phenotype during the initiation of neoplastic development. Two TFs—PTF1a and MIST1—control the specification and maintenance of the differentiated acinar cell state of the pancreas via their expression in the context of self-sustaining “feed-forward” regulatory loops ( 25 ).

Both of these TFs are frequently downregulated during neoplastic development and malignant progression of human and mouse PDAC. Functional genetic studies in mice and cultured human PDAC cells have shown that experimentally forced expression of PTF1a impairs KRAS-induced transdifferentiation and proliferation and can also force the redifferentiation of already neoplastic cells into a quiescent acinar cell phenotype (26).

Conversely, suppression of PTF1a expression triggers acinar-to-duct metaplasia, namely transdifferentiation, and thereby sensitizes the duct-like cells to oncogenic KRAS transformation, accelerating the subsequent development of invasive PDAC ( 27 ). Likewise, forced expression of MIST1 in KRAS-expressing pancreas also blocks transdifferentiation and impairs the initiation of pancreatic tumorigenesis, which is otherwise facilitated by the formation of premalignant duct-like (PanIN) lesions, while genetic deletion of MIST1 enhances their formation and the initiation of KRAS -driven neoplastic progression ( 28 ).

Loss of either PTF1 or MIST1 expression during tumorigenesis is associated with increased expression of another developmental regulatory TF, SOX9, which is normally effective in ductal cell specification (27, 28). Forced upregulation of SOX9, thereby avoiding the need for downregulation of PTF1a, and MIST1 has also been shown to stimulate the transdifferentiation of acinar cells into a ductal cell phenotype sensitive to KRAS-induced neoplasia (29), implicating SOX9 as a key functional effector of their downregulation in the genesis of human PDAC.

Thus, three TFs that regulate pancreatic differentiation can be altered in various ways to induce a transdifferentiated state that, in the context of mutational activation of KRAS, facilitates oncogenic transformation and the initiation of tumorigenesis and malignant progression.

Additional members of the SOX family of chromatin-associated regulatory factors are, on the one hand, largely associated with both cell fate specification and lineage switching in development ( 30 ) and, on the other hand, with several tumor-associated phenotypes ( 31 ). Another prominent example of SOX-mediated transdifferentiation involves a mechanism of therapeutic resistance in prostate cancer.

In this case, loss of the RB and p53 tumor suppressors - the absence of which is characteristic of neuroendocrine tumors - in response to antiandrogen therapy is necessary but not sufficient for the commonly observed transformation of well-differentiated prostate cancer cells into carcinoma cells that have invaded the differentiation lineage with molecular and histological features of neuroendocrine cells that, in particular, do not express the androgen receptor. In addition to loss of RB and p53, acquired resistance to antiandrogen therapy requires upregulated expression of SOX2, a developmental regulatory gene, which has been shown to help induce transdifferentiation of the therapy-responsive adenocarcinoma cells into derivatives that are in a neuroendocrine cell state refractory to therapy (32).

A third example also shows transdifferentiation as a strategy used by carcinoma cells to avoid elimination by lineage-specific therapy, in this case with basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) of the skin treated with a pharmacological inhibitor of the Hedgehog-Smoothened (HH/SMO) oncogenic pathway known to drive the neoplastic growth of these cells ( 33 ).

Drug-resistant cancer cells switch to a developmentally related but distinct cell type via broad epigenetic shifts in specific chromatin domains and altered accessibility of two superenhancers. The newly acquired phenotypic state of BCC cells allows them to maintain expression of the oncogenic WNT signaling pathway, which in turn confers independence from the drug-suppressed HH/SMO signaling pathway (34).

As expected from this transdifferentiation, the transcriptome of the cancer cells shifts from a gene signature reflecting the involved cell of origin of BCCs, namely the hair follicle bulge stem cells, to a signature indicative of the basal stem cells populating the BCC interfollicular epidermis. Such transdifferentiation to enable drug resistance is increasingly documented in various forms of cancer ( 35 ).

Developmental lineage plasticity also appears to be prevalent in the major subtypes of lung carcinoma, i.e. h. in neuroendocrine carcinomas [small cell lung cancer (SCLC)] and adenocarcinomas + squamous cell carcinomas [collective non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)]. Single-cell RNA sequencing has revealed remarkably dynamic and heterogeneous conversion between these subtypes, as well as marked variations therein, during the stages of lung tumorigenesis, subsequent malignant progression, and response to therapy ( 36 – 38 ).

Therefore, rather than the simple conceptualization of a pure clonal switch from one lineage to another, these studies paint a much more complex picture of dynamically interconverting subpopulations of cancer cells that exhibit features of multiple developmental lineages and differentiation stages, a sobering insight in this regard for lineage-based therapeutic targeting of human lung cancer. Regulatory determinants of this dynamic phenotypic plasticity are beginning to be identified ( 37, 39, 40 ).

Summary

The three classes of mechanisms described above highlight selective regulators of cellular plasticity that are – at least partially – separable from core oncogenic drivers and other distinctive capabilities. Beyond these examples, there is a significant body of evidence linking many forms of cancer to impaired differentiation, which is accompanied by the acquisition of transcriptome signatures and other phenotypes - for example, histological morphology - that are associated with progenitor or stem cell stages observed in the corresponding normal tissues. origin or in other more distantly related cell types and lineages ( 41 – 43 ).

As such, these three subclasses of phenotypic plasticity—dedifferentiation of mature cells back to progenitor states, stalled differentiation to freeze developing cells in progenitor/stem cell states, and transdifferentiation to alternative cell lineages—appear to be effective in several cancer types during primary tumorigenesis, malignant progression, and/or response to therapy.

However, there are two conceptual considerations. First, dedifferentiation and stalled differentiation are likely intertwined, as they are indistinguishable in many tumor types in which the cell of origin—differentiated cell or progenitor/stem cell—is either unknown or alternatively involved. Second, the acquisition or maintenance of progenitor cell phenotypes and the loss of differentiated features is, in most cases, an inaccurate reflection of the normal developmental stage, immersing in a milieu of other characteristic changes in the cancer cell that are not present in naturally developing cells.

Furthermore, another form of phenotypic plasticity involves cellular senescence, discussed more generally below, whereby cancer cells induced to undergo seemingly irreversible aging are instead able to escape and continue proliferative expansion (44). Finally, as with other distinctive capabilities, cellular plasticity is not a new invention or aberration of cancer cells, but rather the corruption of latent but activatable capabilities that various normal cells use to support homeostasis, repair, and regeneration ( 45 ).

Overall, these illustrative examples encourage consideration that unlocking cellular plasticity to enable various forms of perturbed differentiation represents a distinct distinctive ability that differs in regulation and cellular phenotype from the well-validated core hallmarks of cancer ( Fig. 2 ).

Epigenetic reprogramming without mutation

The enabling property of genome (DNA) instability and mutation is a fundamental component of cancer development and pathogenesis. Currently, several international consortia are cataloging mutations throughout the genome of human cancer cells, in virtually every type of human cancer, at various stages of malignant progression, including metastatic lesions, and during the development of adaptive therapy resistance. One result is the now widespread recognition that mutations in genes that organize, modulate, and maintain chromatin architecture and thereby regulate gene expression globally are increasingly being discovered and functionally linked to cancer traits ( 46 – 48 ).

Furthermore, there are arguments for another seemingly independent form of genome reprogramming that involves purely epigenetically regulated changes in gene expression, one that could be termed “non-mutational epigenetic reprogramming” ( Fig. 3 ). In fact, the thesis of mutationless cancer evolution and purely epigenetic programming of characteristic cancer phenotypes was raised almost a decade ago ( 49 ) and is increasingly being discussed ( 46, 50–52 ).

Figure 3

Similar to what occurs during embryogenesis and tissue differentiation and homeostasis, accumulating evidence suggests that instrumental gene regulatory circuits and networks in tumors can be controlled by a plethora of corrupted and co-opted mechanisms that are independent of genome instability and gene mutation. The trademarks of the cancer graphic were adopted from Hanahan and Weinberg (2).

Of course, the concept of nonmutational epigenetic regulation of gene expression is well established as the central mechanism mediating embryonic development, differentiation, and organogenesis ( 53 – 55 ). In the adult, for example, long-term memory involves changes in gene and histone modification, in chromatin structure, and in the firing of gene expression switches, which are stably maintained over time by positive and negative feedback loops ( 56, 57 ). Increasing evidence supports the idea that analogous epigenetic changes may contribute to the acquisition of characteristic abilities during tumor development and malignant progression. To support this hypothesis, some examples are presented below.

Microenvironmental mechanisms of epigenetic reprogramming

If not through oncogenic mutations alone, how is the cancer cell genome reprogrammed? A growing body of evidence suggests that the aberrant physical properties of the tumor microenvironment can cause broad changes in the epigenome, of which alterations beneficial for phenotypic selection of trait capabilities can lead to clonal outgrowth of cancer cells with improved fitness for proliferative expansion.

A common feature of tumors (or regions within tumors) is hypoxia as a result of inadequate vascularization. Hypoxia, for example, reduces the activity of TET demethylases, leading to significant changes in the methylome, particularly hypermethylation ( 58 ). Insufficient vascularization is also likely to limit the bioavailability of critical blood-borne nutrients, and nutrient deprivation, for example, has been shown to alter translational control and consequently increase the malignant phenotype of breast cancer cells ( 59 ).

A compelling example of hypoxia-mediated epigenetic regulation is a form of the invariably fatal pediatric ependymoma. Like many embryonic and pediatric tumors, this form lacks recurrent mutations, particularly a lack of driver mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Rather, the abnormal growth of these cancer cells has been shown to be controlled by a hypoxia-induced gene regulatory program ( 60, 61 ). Remarkably, the putative cell of origin of this cancer resides in a hypoxic compartment and likely sensitizes cells within it to initiate tumorigenesis through as yet unknown cofactors.

Another compelling evidence for microenvironment-mediated epigenetic regulation concerns the invasive growth ability of cancer cells. A classic example is the reversible induction of invasiveness of cancer cells at the edges of many solid tumors, orchestrated by the developmental regulatory program known as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT; refs. 62–64 ). Notably, a master regulator of EMT, ZEB1, was recently shown to induce the expression of a histone methyltransferase, SETD1B, which in turn maintains ZEB1 expression in a positive feedback loop that maintains the (invasive) regulatory state of EMT (65).

A previous study similarly documented that induction of EMT through upregulated expression of a related TF, SNAIL1, caused marked changes in the chromatin landscape as a result of the induction of a number of chromatin modifiers whose activity was shown to be necessary for the maintenance of the phenotypic state ( 66 ). Furthermore, a number of conditions and factors experienced by cancer cells at the edges of tumors, including hypoxia and cytokines secreted by stromal cells, can apparently induce EMT and thus invasiveness ( 67, 68 ).

A striking example of programming of invasiveness by the microenvironment, supposedly unrelated to the EMT program, involves the autocrine activation of a neuronal signaling circuit involving secreted glutamate and its receptor NMDAR ( 69 , 70 ). Remarkably, the prototypical stiffness of many solid tumors, embodied in extensive alterations to the extracellular matrix (ECM) that encases the cells within them, has profound implications for the invasive and other phenotypic properties of cancer cells.

Compared to the normal tissue ECM from which tumors arise, the tumor ECM is typically characterized by increased cross-linking and density, enzymatic modifications, and altered molecular composition that collectively orchestrate, in part through integrin receptors for ECM motifs, stiffness-induced signaling and gene expression networks that induce invasiveness and other characteristic features ( 71 ).

In addition to such regulatory mechanisms endowed by the physical tumor microenvironment, paracrine signaling, comprising soluble factors released into the extracellular milieu by the various cell types that populate solid tumors, can also contribute to the induction of several morphologically distinct invasive growth programs ( 72 ), only one of which – termed “mesenchymal” – appears to be involved in the above-mentioned epigenetic regulatory mechanism of EMT.

Epigenetic regulatory heterogeneity

A growing knowledge base increases appreciation for the importance of intratumoral heterogeneity in generating the phenotypic diversity where the most suitable cells for proliferative expansion and invasion outgrow their brethren and are therefore selected for malignant progression. Certainly, one facet of this phenotypic heterogeneity is due to chronic or episodic genomic instability and resulting genetic heterogeneity in the cells that populate a tumor.

Furthermore, it is becoming increasingly clear that non-mutation-based epigenetic heterogeneity may exist. A prominent example is the linker histone H1.0, which is dynamically expressed and repressed in subpopulations of cancer cells within a range of tumor types, with consequent sequestration or accessibility of megabase-sized domains [73]. Notably, the population of cancer cells with repressed H1.0 was found to exhibit stem-like properties, enhanced tumor-initiating ability and an association with poor prognosis in patients.

Another example of epigenetically regulated plasticity has been described in human oral squamous cell carcinomas (SCC), where cancer cells at the invasive margins adopt a partial EMT state (p-EMT) that lacks the aforementioned mesenchymal TFs but expresses other EMT-defining genes that are not expressed in the central core of the tumors (74).

The p-EMT cells obviously do not represent clonal compartmentalization of mutationally altered cells: cultures of primary tumor-derived cancer cells contain dynamic mixtures of both p-EMT hi and p-EMT lo cells and when p-EMT hi/lo cells were FACS purified and cultured, both reverted to mixed populations of p-EMT hi and p-EMT lo within 4 days. Although paracrine signals from the adjacent stroma could be considered deterministic for the p-EMT hi state, the stable presence and regeneration of the two epigenetic states in culture argues for a cancer cell-intrinsic mechanism. Notably, this conclusion is supported by the analysis of 198 cell lines representing 22 cancer types, including SCC, where 12 stably heterogeneous epigenetic states (including the p-EMT in SCC) were variously detected in the cell line models as well as their related primary tumors ( 75 ).

Again, the heterogeneous phenotypic states could not be linked to detectable genetic differences, and in several cases FACS-sorted cells of a particular state have been shown to dynamically re-equilibrate upon culture, recapitulating a stable equilibrium between the heterogeneous states observed in the original cell lines.

Furthermore, technologies for genome-wide profiling of various attributes—beyond the DNA sequence and its mutational variation—illuminate influential elements of the annotation and organization of the cancer cell genome that correlate with patient prognosis and, increasingly, with characteristic abilities ( 76 – 78 ). Epigenomic heterogeneity is being revealed by increasingly powerful technologies for profiling genome-wide DNA methylation ( 79, 80 ), histone modification ( 81 ), chromatin accessibility ( 82 ), and post-transcriptional modification and translation of RNA ( 83, 84 ).

A challenge with respect to the postulate considered here will be to determine which epigenomic modifications in certain cancer types (i) have regulatory significance and (ii) are representative of purely non-mutational reprogramming, as opposed to mutation-driven and thus genome-explainable instability.

Epigenetic regulation of stromal cell types populating the tumor microenvironment

In general, the accessory cells in the tumor microenvironment that functionally contribute to the acquisition of characteristic abilities are not thought to suffer from genetic instability and mutational reprogramming to enhance their tumor-promoting activities; rather, it is concluded that these cells—cancer-associated fibroblasts, innate immune cells, and endothelial cells and pericytes of the tumor vasculature—are epigenetically reprogrammed upon their recruitment by soluble and physical factors that define the solid tumor microenvironment ( 2 , 85 ).

It is expected that the multi-omic profiling technologies currently applied to cancer cells will be increasingly used to study the accessory (stromal) cells in tumors to elucidate how normal cells are damaged to functionally support tumor development and progression. For example, a recent study (86) suggests that such reprogramming may involve modifications of the epigenome, in addition to the inductive exchange of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors that alter intracellular signaling networks in all of these cell types:

When mouse models with lung metastases were treated with a combination of a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor (5-azacytidine) and a histone modification inhibitor (an HDAC), the infiltrating myeloid cells were found to have transitioned from an immature (tumor-promoting) progenitor state into cells resembling mature interstitial (tumor-antagonizing) macrophages, which, unlike their counterparts in untreated tumors, were unable to to support the typical capabilities required for efficient metastatic colonization ( 86). It is conceivable that multi-omic profiling and pharmacological perturbations will serve to elucidate the reprogrammed epigenetic state in such myeloid cells as well as other characteristic accessory cell types that populate tumor microenvironments.

Summary

Taken together, these illustrative snapshots support the thesis that epigenetic reprogramming without mutation will be accepted as a true enabling trait that serves to facilitate the acquisition of characteristic abilities ( Fig. 3 ), distinct from genomic DNA instability and mutation. In particular, non-mutational epigenetic reprogramming can be expected to prove integral to enabling the preliminary new distinctive ability of phenotypic plasticity discussed above, particularly as a driving force in the dynamic transcriptomic heterogeneity that is increasingly well documented in malignant cancer cell TMEs. The advancement of single-cell multi-omic profiling technologies will shed light on the respective contributions and interplay between mutation-driven and non-mutation-driven epigenetic regulation in the development of tumors during malignant progression and metastasis.

Polymorphic microbiomes

A far-reaching frontier in biomedicine is unfolding by illuminating the diversity and variability of the abundance of microorganisms, collectively referred to as the microbiota, that associate symbiotically with the body's barrier tissues exposed to the external environment - particularly the epidermis and internal mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract, as well as the lungs, breast and genitourinary system.

There is increasing recognition that the ecosystems created by resident bacteria and fungi—the microbiomes—have profound effects on health and disease ( 87 ), a realization driven by the ability to screen the populations of microbial species using next-generation sequencing and bioinformatics technologies. For cancer, evidence is becoming increasingly compelling that polymorphic variability in the microbiomes between individuals in a population can have profound effects on cancer phenotypes ( 88 , 89 ).

Association studies in human and experimental manipulations in mouse models of cancer reveal certain microorganisms, primarily but not exclusively bacteria, that may have either protective or detrimental effects on cancer development, malignant progression, and response to therapy. This also applies to the global complexity and composition of a tissue microbiome as a whole. While the gut microbiome was the pioneer of this new frontier, several tissues and organs have associated microbiomes that exhibit distinctive features related to population dynamics and the diversity of microbial species and subspecies.

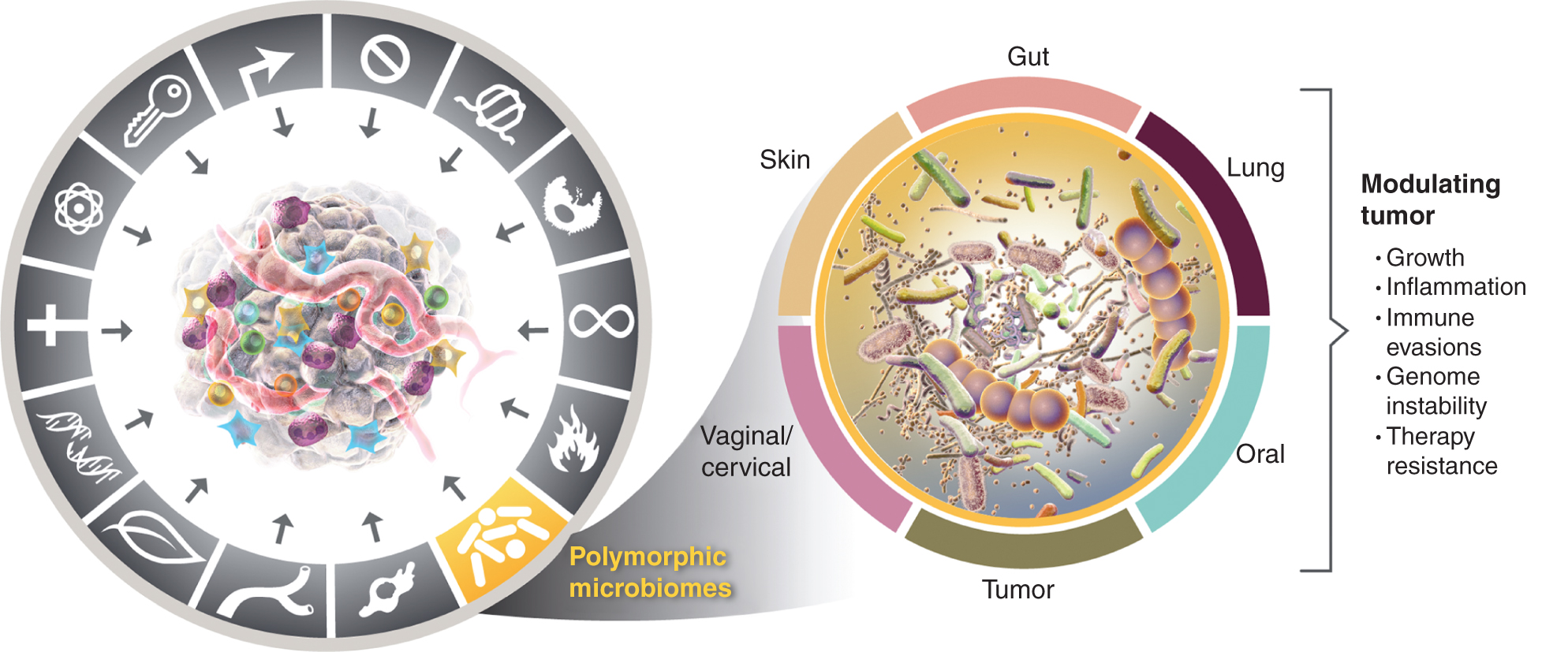

This growing appreciation of the importance of polymorphically variable microbiomes in health and disease raises the question: Is the microbiome a distinct enabling trait that broadly impacts, both positively and negatively, the acquisition of distinctive capabilities for cancer? I consider this possibility below and illustrate evidence for some of the prominent tissue microbiomes implicated in cancer traits (Fig. 4), starting with the most prominent and apparently most impactful microbiome, that of the intestinal tract.

Figure 4

Left, while the enabling properties of tumor-promoting inflammation and genomic instability and mutation overlap, there is increasing reason to conclude that polymorphic microbiomes located in one individual compared to another in the colon, in other mucous membranes and associated organs, or in tumors themselves, can influence many of the characteristic abilities in a variety of ways - either through induction or inhibition - and therefore may be an instrumental and quasi-independent variable in the puzzle of how cancer develops, progresses and grows responds to therapy. True, multiple tissue microbiomes are involved in modulating tumor phenotypes. In addition to the widely studied gut microbiome, other characteristic tissue microbiomes as well as the tumor microbiome are involved in modulating the acquisition - both positive and negative - of the characteristic abilities presented in certain tumor types. The trademarks of the cancer graphic were adopted from Hanahan and Weinberg (2).

Multiple modulatory effects of the intestinal microbiome

It has long been known that the gut microbiome is fundamental to the function of the large intestine (colon) in breaking down and importing nutrients into the body as part of metabolic homeostasis, and that disruption of microbial populations—dysbiosis—in the colon can cause a spectrum of physiological diseases (87). This includes the suspicion that the susceptibility, development and pathogenesis of colon cancer is influenced by the intestinal microbiome. In recent years, convincing functional studies using fecal transplants from colon tumor-bearing patients and mice into recipient mice predisposed to the development of colon cancer have established a principle: there are both cancer-protective and tumor-promoting microbiomes involving specific bacterial species that can modulate the occurrence and pathogenesis of colon tumors (90).

The mechanisms by which microbiota confer these modulatory roles are still being elucidated, but two general effects are increasingly well established for tumor-promoting microbiomes and, in some cases, for specific tumor-promoting bacterial species. The first effect is mutagenesis of the colonic epithelium as a result of the production of bacterial toxins and other molecules that either directly damage DNA or disrupt the systems that maintain genomic integrity or otherwise stress cells, indirectly affecting the fidelity of DNA replication and repair. A typical example is E. coli, which carries the PKS locus, which has been shown to mutagenize the human genome and is involved in the transmission of mutations that enable the mark (91).

Furthermore, bacteria have been reported to bind to the surface of colonic epithelial cells and produce ligand mimetics that stimulate epithelial proliferation, contributing to the characteristic proliferative signaling ability in neoplastic cells ( 88 ). Another mechanism by which specific types of bacteria promote tumor development are butyrate-producing bacteria, whose abundance is increased in patients with colorectal cancer (92).

Production of the metabolite butyrate has complex physiological effects, including the induction of senescent epithelial and fibroblast cells. A mouse model of colon carcinogenesis colonized with butyrate-producing bacteria developed more tumors than mice lacking such bacteria; The connection between butyrate-induced senescence and increased colon tumorigenesis has been demonstrated through the use of a senolytic drug that kills senescent cells, impairing tumor growth ( 92 ).

Furthermore, bacterially produced butyrate has pleiotropic and paradoxical effects on differentiated cells compared to undifferentiated (stem) cells in the colonic epithelium in conditions where the intestinal barrier is disrupted (dysbiosis) and the bacteria are invasive, affecting, for example, cellular energy and metabolism, histone modification, cell cycle progression, and (tumor-promoting) innate immune inflammation that immunosuppresses adaptive immune responses (93).

Indeed, a broad action of polymorphic microbiomes involves the modulation of the adaptive and innate immune systems through diverse pathways, including the production of “immunomodulatory” factors by bacteria that activate damage sensors on epithelial or resident immune cells, leading to the expression of a diverse repertoire of chemokines and cytokines that can shape the abundance and properties of immune cells populating the colonic epithelium and the underlying stroma and draining lymph nodes.

In addition, certain bacteria can breach both the protective biofilm and mucus lining the colonic epithelium and disrupt the epithelial cell-cell tight junctions that collectively maintain the integrity of the physical barrier that normally compartmentalizes the gut microbiome. Upon invading the stroma, bacteria can trigger both innate and adaptive immune responses by eliciting the secretion of a repertoire of cytokines and chemokines. One manifestation may be the creation of tumor-promoting or tumor-antagonizing immune microenvironments, which consequently protect against or facilitate tumorigenesis and malignant progression.

Accordingly, the modulation of the intertwined parameters of (i) the induction of (innate) tumor-promoting inflammation and (ii) the escape from (adaptive) immune destruction by characteristic microbiomes in individual patients may be associated not only with prognosis but also with response or resistance to immunotherapies with immune checkpoint inhibitors and other therapeutic modalities (One manifestation may be the creation of tumor-promoting or tumor-antagonizing immune microenvironments, which consequently occur Protect or facilitate tumor development and malignant progression.

Accordingly, the modulation of the intertwined parameters of (i) the induction of (innate) tumor-promoting inflammation and (ii) the escape from (adaptive) immune destruction by characteristic microbiomes in individual patients may be associated not only with prognosis but also with response or resistance to immunotherapies with immune checkpoint inhibitors and other therapeutic modalities (One manifestation may be the creation of tumor-promoting or tumor-antagonizing immune microenvironments, which consequently occur protect or facilitate tumor development and malignant progression).

Accordingly, modulation of the intertwined parameters of (i) induction of (innate) tumor-promoting inflammation and (ii) escape from (adaptive) immune destruction by distinctive microbiomes in individual patients may be associated not only with prognosis but also with response or resistance to immunotherapies with immune checkpoint inhibitors and other therapeutic modalities (89, 94–96). Preliminary proof-of-concept comes from recent studies showing restored efficacy of immunotherapy after transplants of fecal microbiota from therapy-responders into patients with melanoma that had progressed during prior treatment with immune checkpoint blockade ( 97, 98 ).

The molecular mechanisms by which distinct and variable components of the gut microbiome systemically modulate the activity of the adaptive immune system remain a persistent mystery, either by enhancing antitumor immune responses elicited by immune checkpoint blockade or, rather, by inducing systemic or local (intratumoral) immunosuppression. A recent study has shed light: certain strains of Enterococcus (and other bacteria) express a peptidoglycan hydrolyase called SagA, which releases mucopeptides from the bacterial wall, which can then circulate systemically and activate the NOD2 pattern receptor, which in turn increases T-cell responses and the effectiveness of checkpoint immunotherapy (99).

Other immunoregulatory molecules produced by specific bacterial subspecies are identified and functionally assessed, including bacterial-produced inosine, a rate-limiting metabolite for T cell activity ( 100 ). These and other examples begin to delineate the molecular mechanisms by which polymorphic microbiomes indirectly and systemically modulate tumor immunobiology, above and beyond immune responses that follow direct physical interactions of bacteria with the immune system (101, 102).

Aside from the causal links to colon cancer and melanoma, the demonstrated ability of the gut microbiome to elicit the expression of immunomodulatory chemokines and cytokines that enter the systemic circulation is also apparently capable of influencing cancer pathogenesis and response to therapies in other organs of the body (94, 95).

An illuminating example concerns the development of cholangiocarcinomas in the liver: intestinal dysbiosis allows entry and transport of bacteria and bacterial products through the portal vein to the liver, where TLR4 expressed on hepatocytes is triggered to induce expression of the chemokine CXCL1, which recruits CXCR2-expressing granulocytic myeloid cells (gMDSC) that serve to suppress natural killer cells to evade immune destruction (103) and probably convey other distinctive abilities (85). As such, the gut microbiome is clearly implicated as an enabling feature that may alternatively facilitate or protect against multiple cancers.

Beyond the gut: Implicating distinct microbiomes in other barrier tissues

Almost all tissues and organs that are directly or indirectly exposed to the external environment are also repositories of commensal microorganisms ( 104 ). In contrast to the gut, where the symbiotic role of the microbiome in metabolism is well recognized, the normal and pathogenic roles of the resident microbiota in these diverse locations are still emerging.

There are apparent organ/tissue-specific differences in the constitution of the associated microbiomes in homeostasis, aging, and cancer, with both overlapping and distinctive species and frequencies to those of the colon ( 104 , 105 ). Furthermore, association studies are providing increasing evidence that local tumor-antagonizing/protective versus tumor-promoting tissue microbiomes, similar to the gut microbiome, can modulate susceptibility and pathogenesis to human cancers arising in their associated organs ( 106 – 109 ).

Influence of the intratumoral microbiota?

Finally, pathologists have long recognized that bacteria can be detected in solid tumors, an observation that has now been substantiated by sophisticated profiling technologies. For example, in a study of 1,526 tumors spanning seven human cancer types (bone, brain, breast, lung, melanoma, ovary, and pancreas), each type was characterized by a distinctive microbiome, located largely in cancer cells and immune cells. Within each tumor type, variations in the tumor microbiome have been demonstrated and concluded to be associated with clinicopathological features (110).

Microbiota have similarly been detected in de novo genetically engineered mouse models of lung and pancreatic cancer, and their absence in germ-free mice and/or their abrogation with antibiotics can be shown to impair tumorigenesis, functionally implicating the tumor microbiome as a precursor to tumor-promoting inflammation and malignant progression (111, 112).

Association studies in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and functional assays via fecal transplantation into tumor-bearing mice have shown that variations in the tumor microbiome—and the associated gut microbiome—modulate immune system phenotypes and survival ( 113 ). An important challenge for the future will be to extend these implications to other tumor types and to disentangle the potentially separable contributions of constitution and variation in the tumor microbiome from those of the gut microbiome (and the local tissue of origin), perhaps by identifying specific microbial species that are functionally influential at one site or another.

Summary

Intriguing questions for the future include whether microbiota residing in different tissues or populating incipient neoplasms have the ability to contribute to or disrupt the acquisition of other distinctive capabilities beyond immunomodulation and genomic mutation, thereby influencing tumor development and progression. There is evidence that certain bacterial species can directly stimulate the hallmark of proliferative signaling, for example in the colonic epithelium (88), and can modulate growth suppression by altering tumor suppressor activity in different compartments of the intestine (114), while direct effects on other characteristic abilities, such as avoiding cell death, triggering angiogenesis, and stimulating invasion and metastasis, remain unclear, as well the generalizability of these observations to multiple forms of human cancer.

Regardless, there are increasingly compelling arguments that polymorphic variation in the microbiomes of the gut and other organs represents a distinctive activating feature for the acquisition of distinctive skills (Fig. 4), even as it overlaps with and complements those of genome instability and mutation, and tumor-promoting inflammation.

Senescent cells

Cellular senescence is a typically irreversible form of proliferative arrest that likely evolved as a protective mechanism to maintain tissue homeostasis, ostensibly as a complementary mechanism to programmed cell death that serves to inactivate and, in due course, remove diseased, dysfunctional, or otherwise unnecessary cells. In addition to shutting down the cell division cycle, the senescence program produces changes in cell morphology and metabolism and, most profoundly, the activation of a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which involves the release of a plethora of bioactive proteins, including chemokines.

Cytokines and proteases, the identity of which depends on the cell and tissue type from which a senescent cell arises ( 115–117). Senescence can be induced in cells by a variety of conditions, including microenvironmental stresses such as nutrient starvation and DNA damage, as well as damage to organelles and cellular infrastructure and imbalances in cellular signaling networks ( 115, 117 ), all of which have occurred in the context of the observed increase in the frequency of senescent cells in various organs during aging ( 118, 119 ).

Cellular senescence has long been considered a protective mechanism against neoplasia, causing cancer cells to undergo senescence ( 120 ). Most of the above-mentioned initiators of the senescence program are associated with malignancy, especially DNA damage as a result of aberrant hyperproliferation, so-called oncogene-induced senescence due to hyperactivated signaling and therapy-induced senescence as a result of cellular and genomic damage caused by chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Indeed, there are well-established examples of the protective benefits of senescence in limiting malignant progression ( 118 , 119 ). On the contrary, however, a growing body of evidence shows just the opposite: in certain contexts, senescent cells differentially stimulate tumor development and malignant progression (119, 121).

In an insightful case study, senescent cells in aging mice were pharmacologically ablated, specifically depleting senescent cells that characteristically express the cell cycle inhibitor p16 – INK4a: in addition to delaying several age-related symptoms, this resulted in depletion of senescent cells in aging mice with reduced incidences of spontaneous tumorigenesis and cancer-associated death (122).

The main mechanism by which senescent cells promote tumor phenotypes is thought to be the SASP, which has been shown to be able to mediate signaling molecules (and proteases that activate and/or deactivate) in a paracrine manner to mediate typical capabilities. Thus, in various experimental systems, senescent cancer cells have been shown to contribute in various ways to proliferative signaling, avoid apoptosis, induce angiogenesis, stimulate invasion and metastasis, and suppress tumor immunity ( 116 , 118 , 120 , 121 ).

Yet another facet of the effects of senescent cancer cells on cancer phenotypes involves transient, reversible senescent cell states, whereby senescent cancer cells can escape their SASP-expressing, nonproliferative state and resume cell proliferation and manifestation of the associated capabilities of a fully viable oncogene cells (44).

Such transient senescence is best documented in cases of therapy resistance (44), which represents a form of quiescence that evades therapeutic targeting of proliferating cancer cells, but may prove more broadly effective in other stages of tumor development, malignant progression, and metastasis.

Furthermore, the hallmark-promoting abilities of senescent cells are not limited to senescent cancer cells. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) have been shown to senesce in tumors, giving rise to senescent CAFs that have been shown to be tumor-promoting by conferring characteristic abilities to cancer cells in the TME ( 115 , 116 , 121 ).

Furthermore, senescent fibroblasts in normal tissues, formed in part by natural aging or environmental insults, are similarly involved in remodeling tissue microenvironments via their SASP to provide paracrine support for local invasion (so-called “field effects”) and distant metastasis (116) of neoplasms developing nearby.

Furthermore, senescent fibroblasts in aging skin have been shown to recruit—via their SASP—innate immune cells that are both immunosuppressive of adaptive antitumor immune responses anchored by CD8 T cells and stimulate skin tumor growth (123), the latter effect possibly reflecting paracrine contributions of such innate immune cells (myeloid cells, neutrophils, and macrophages) to other characteristic capabilities reflects.

Although less well established, it seems likely that other abundant stromal cells populating specific tumor microenvironments will undergo senescence, thereby modulating cancer characteristics and resulting tumor phenotypes. For example, therapy-induced senescent tumor endothelial cells can enhance proliferation, invasion, and metastasis in breast cancer models ( 124 , 125 ).

Certainly, such evidence warrants investigation in other tumor types to evaluate general senescence of fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and other stromal cells as a driving force in tumor development. Also currently unclear are the regulatory mechanisms and functional determinants by which a particular senescent cell type in a particular TME elicits a tumor-promoting versus a tumor-antagonizing SASP, which apparently can be induced alternatively in the same senescent cell type, perhaps by different initiators when immersed in characteristic physiological and neoplastic microenvironments.

Summary

The concept that tumors consist of genetically transformed cancer cells that interact with and benefit from recruited and epigenetically/phenotypically corrupted accessory (stromal) cells has been established as crucial to the pathogenesis of cancer. The considerations discussed above and described in the reviews and reports cited here (and elsewhere) argue convincingly that senescent cells (regardless of cellular origin) should be considered for inclusion in the list of functionally significant cells in the tumor microenvironment (Fig. 5). Therefore, senescent cells should be considered in the search for in-depth knowledge of cancer mechanisms. Furthermore, the recognition of their importance motivates the secondary goal of therapeutically targeting tumor-promoting senescent cells of all constitutions, be it through pharmacological or immunological ablation or by reprogramming the SASP into tumor-antagonizing variants ( 115 , 121 , 126 ).

Figure 5

Heterogeneous cancer cell subtypes and stromal cell types and subtypes are functionally integrated into the manifestations of tumors as illegal organs. Increasing evidence suggests that senescent cell derivatives of many of these cellular components of the TME and their variable SASPs are involved in the modulation of hallmark capabilities and resulting tumor phenotypes. The trademarks of the cancer graphic were adopted from Hanahan and Weinberg (2).

Concluding remarks

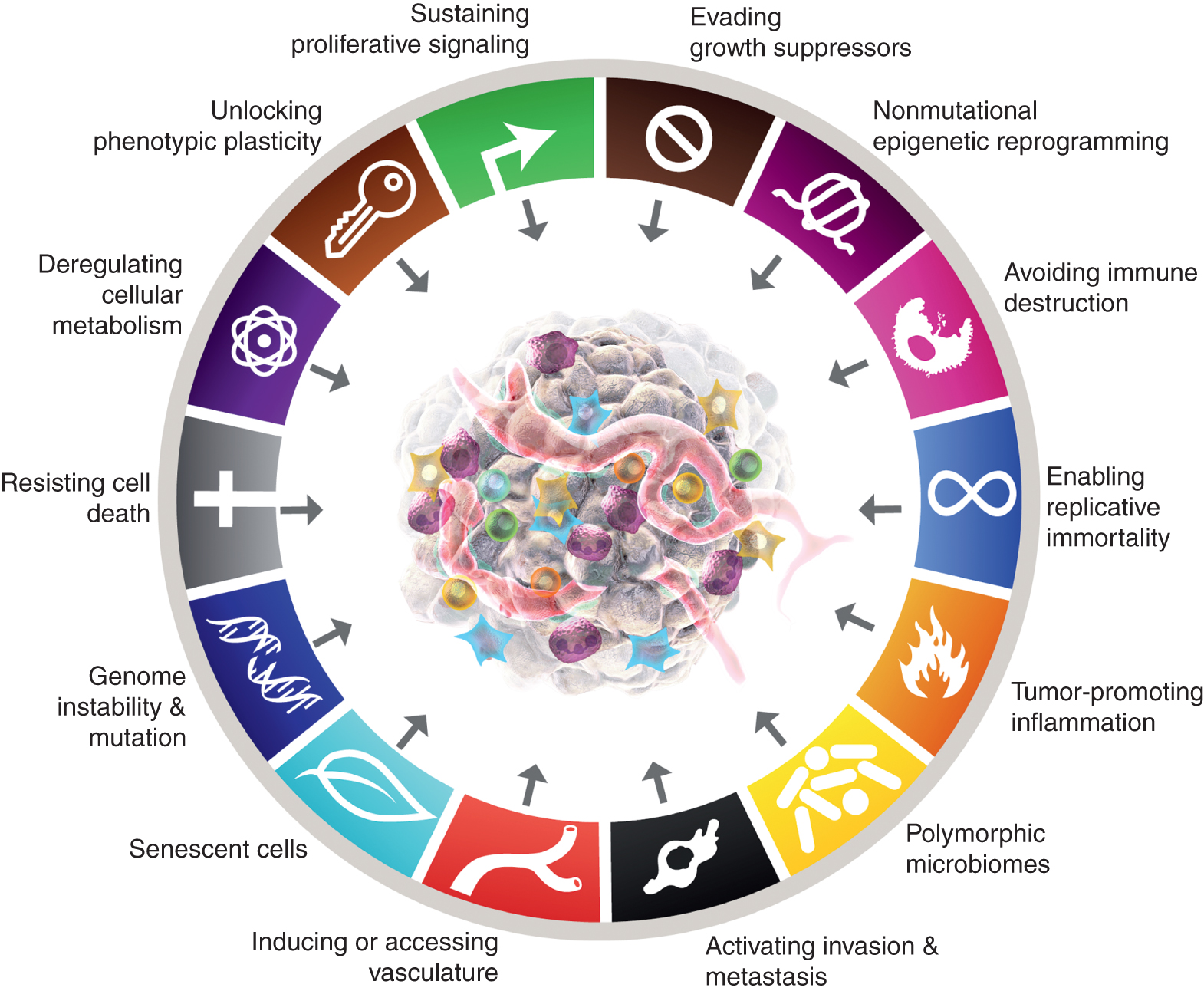

While the eight hallmarks of cancer and their two supporting features have proven to have enduring heuristic value in the conceptualization of cancer, the considerations presented above suggest that there may be new facets of some generality and therefore importance for a more complete understanding of the complexities, mechanisms, and manifestations of the disease. By applying the metric of discernible, if not complete, independence from the 10 core attributes, it is arguable that these four parameters - upon further validation and generalization beyond the case studies presented - may well be integrated into the hallmarks of the cancer schema (Fig. 6).

Therefore, cellular plasticity could be added to the list of prominent capabilities. While the eighth core and this nouveau ability are each conceptually distinguishable by their definition as hallmarks, aspects of their regulation are at least partially linked in some and perhaps many cancers. For example, multiple hallmarks are coordinately modulated by canonical oncogenic drivers in some tumor types, including

- (I) KRAS ( https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic/census-page/KRAS ),

- (II) MYC ( https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic/census-page/MYC ),

- (III) NOTCH ( https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic/census-page/NOTCH1 ; Ref. 127) und

- (IV) TP53 ( https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic/census-page/TP53 )

Figure 6

The canonical and expected new additions to the “Hallmarks of Cancer” are shown. This paper raises the possibility, with the aim of stimulating debate, discussion and experimental elaboration, that some or all of the four new parameters will be recognized as generic to multiple forms of human cancer and therefore suitable for integration into the core conceptualization of the hallmarks of cancer. The trademarks of the cancer graphic were adopted from Hanahan and Weinberg (2).

In addition to adding cellular plasticity to the roster, non-mutational epigenetic reprogramming and polymorphic variations can be integrated into organ/tissue microbiomes as mechanistic determinants – enabling properties – through which distinctive capabilities are acquired, along with tumor-promoting inflammation (itself partially interconnected to the microbiome), beyond the mutations and other aberrations that manifest the oncogenic drivers mentioned above.

Finally, senescent cells of diverse origins—including cancer cells and various stromal cells—that functionally contribute to the development and malignant progression of cancer, albeit in markedly different ways from those of their non-senescent brethren, can be included as generic components of the TME. In summary, it is envisaged that the deployment of these preliminary “experimental balloons” will stimulate debate, discussion and further experimental investigation in the cancer research community on the defining conceptual parameters of cancer biology, genetics and pathogenesis.

References

- Hanahan D , Weinberg RA . The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000;100:57–70.

- Hanahan D , Weinberg RA . Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011;144:646–74.

- Yuan S , Norgard RJ , Stanger BZ . Cellular plasticity in cancer. Cancer Discov 2019;9:837–51.

- Barker N , Ridgway RA , van Es JH , van de Wetering M , Begthel H , van den Born M et al . Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature 2009;457:608–11.

- Perekatt AO , Shah PP , Cheung S , Jariwala N , Wu A , Gandhi V et al . SMAD4 suppresses WNT-driven dedifferentiation and oncogenesis in the differentiated gut epithelium. Cancer Res 2018;78:4878–90.

- Shih IM , Wang TL , Traverso G , Romans K , Hamilton SR , Ben-Sasson S et al . Top-down morphogenesis of colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:2640–5.

- Ordóñez-Morán P , Dafflon C , Imajo M , Nishida E , Huelsken J . HOXA5 counteracts stem cell traits by inhibiting Wnt signaling in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell 2015;28:815–29.

- Tan SH , Barker N . Stemming colorectal cancer growth and metastasis: HOXA5 forces cancer stem cells to differentiate. Cancer Cell 2015;28:683–5.

- Köhler C , Nittner D , Rambow F , Radaelli E , Stanchi F , Vandamme N et al . Mouse cutaneous melanoma induced by mutant BRaf arises from expansion and dedifferentiation of mature pigmented melanocytes. Cell Stem Cell 2017;21:679–93.

- Shah M , Bhoumik A , Goel V , Dewing A , Breitwieser W , Kluger H et al . A role for ATF2 in regulating MITF and melanoma development. PLoS Genet 2010;6:e1001258.

- Claps G , Cheli Y , Zhang T , Scortegagna M , Lau E , Kim H et al . A transcriptionally inactive ATF2 variant drives melanomagenesis. Cell Rep 2016;15:1884–92.

- Saghafinia S , Homicsko K , Di Domenico A , Wullschleger S , Perren A , Marinoni I et al . Cancer cells retrace a stepwise differentiation program during malignant progression. Cancer Discov 2021;11:2638–57.

- Yu X-X , Qiu W-L , Yang L , Zhang Y , He M-Y , Li L-C et al . Defining multistep cell fate decision pathways during pancreatic development at single-cell resolution. EMBO J 2019;38:e100164.

- de Thé H . Differentiation therapy revisited. Nat Rev Cancer 2018;18:117–27.

- He LZ , Merghoub T , Pandolfi PP . In vivo analysis of the molecular pathogenesis of acute promyelocytic leukemia in the mouse and its therapeutic implications. Oncogene 1999;18:5278–92.

- Warrell RP , de Thé H , Wang ZY , Degos L . Acute promyelocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med 1993;329:177–89.

- Bots M , Verbrugge I , Martin BP , Salmon JM , Ghisi M , Baker A et al . Differentiation therapy for the treatment of t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia using histone deacetylase inhibitors. Blood 2014;123:1341–52.

- Ferrara FF , Fazi F , Bianchini A , Padula F , Gelmetti V , Minucci S et al . Histone deacetylase-targeted treatment restores retinoic acid signaling and differentiation in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Res 2001;61:2–7.

- Kaufman CK , Mosimann C , Fan ZP , Yang S , Thomas AJ , Ablain J et al . A zebrafish melanoma model reveals emergence of neural crest identity during melanoma initiation. Science 2016;351:aad2197.

- Morris JP , Yashinskie JJ , Koche R , Chandwani R , Tian S , Chen C-C et al . α-Ketoglutarate links p53 to cell fate during tumour suppression. Nature 2019;573:595–9.

- Saha SK , Parachoniak CA , Ghanta KS , Fitamant J , Ross KN , Najem MS et al . Mutant IDH inhibits HNF-4α to block hepatocyte differentiation and promote biliary cancer. Nature 2014;513:110–4.

- Dang L , Su S-SM . Isocitrate dehydrogenase mutation and (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate: from basic discovery to therapeutics development. Annu Rev Biochem 2017;86:305–31.

- Waitkus MS , Diplas BH , Yan H . Biological role and therapeutic potential of IDH mutations in cancer. Cancer Cell 2018;34:186–95.

- Phan TG , Croucher PI . The dormant cancer cell life cycle. Nat Rev Cancer 2020;20:398–411.

- Jiang M , Azevedo-Pouly AC , Deering TG , Hoang CQ , DiRenzo D , Hess DA et al . MIST1 and PTF1 collaborate in feed-forward regulatory loops that maintain the pancreatic acinar phenotype in adult mice. Mol Cell Biol 2016;36:2945–55.

- Krah NM , Narayanan SM , Yugawa DE , Straley JA , Wright CVE , MacDonald RJ et al . Prevention and reversion of pancreatic tumorigenesis through a differentiation-based mechanism. Dev Cell 2019;50:744–54.

- Krah NM , De La O J-P , Swift GH , Hoang CQ , Willet SG , Chen Pan F et al . The acinar differentiation determinant PTF1A inhibits initiation of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. eLife 2015;4:e07125.

- Shi G , DiRenzo D , Qu C , Barney D , Miley D , Konieczny SF . Maintenance of acinar cell organization is critical to preventing Kras-induced acinar-ductal metaplasia. Oncogene 2013;32:1950–8.

- Kopp JL , von Figura G , Mayes E , Liu F-F , Dubois CL , Morris JP et al . Identification of Sox9-dependent acinar-to-ductal reprogramming as the principal mechanism for initiation of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2012;22:737–50.

- Julian LM , McDonald AC , Stanford WL . Direct reprogramming with SOX factors: masters of cell fate. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2017;46:24–36.

- Grimm D , Bauer J , Wise P , Krüger M , Simonsen U , Wehland M et al . The role of SOX family members in solid tumours and metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol 2020;67:122–53.

- Mu P , Zhang Z , Benelli M , Karthaus WR , Hoover E , Chen C-C et al . SOX2 promotes lineage plasticity and antiandrogen resistance in TP53- and RB1-deficient prostate cancer. Science 2017;355:84–8.

- Von Hoff DD , LoRusso PM , Rudin CM , Reddy JC , Yauch RL , Tibes R et al . Inhibition of the hedgehog pathway in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1164–72.

- Biehs B , Dijkgraaf GJP , Piskol R , Alicke B , Boumahdi S , Peale F et al . A cell identity switch allows residual BCC to survive Hedgehog pathway inhibition. Nature 2018;562:429–33.

- Boumahdi S , de Sauvage FJ . The great escape: tumour cell plasticity in resistance to targeted therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2020;19:39–56.

- Groves SM , Ireland A , Liu Q , Simmons AJ , Lau K , Iams WT et al . Cancer Hallmarks Define a Continuum of Plastic Cell States between Small Cell Lung Cancer Archetypes [Internet]. Systems Biology; 2021 Jan. Available from: http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2021.01.22.427865.

- LaFave LM , Kartha VK , Ma S , Meli K , Del Priore I , Lareau C et al . Epigenomic state transitions characterize tumor progression in mouse lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2020;38:212–28.

- Marjanovic ND , Hofree M , Chan JE , Canner D , Wu K , Trakala M et al . Emergence of a high-plasticity cell state during lung cancer evolution. Cancer Cell 2020;38:229–46.

- Drapkin BJ , Minna JD . Studying lineage plasticity one cell at a time. Cancer Cell 2020;38:150–2.

- Inoue Y , Nikolic A , Farnsworth D , Liu A , Ladanyi M , Somwar R et al . Extracellular signal-regulated kinase mediates chromatin rewiring and lineage transformation in lung cancer [Internet]. Cancer Biology; 2020 Nov. Available from: http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2020.11.12.368522.

- Dravis C , Chung C-Y , Lytle NK , Herrera-Valdez J , Luna G , Trejo CL et al . Epigenetic and transcriptomic profiling of mammary gland development and tumor models disclose regulators of cell state plasticity. Cancer Cell 2018;34:466–82.

- Malta TM , Sokolov A , Gentles AJ , Burzykowski T , Poisson L , Weinstein JN et al . Machine learning identifies stemness features associated with oncogenic dedifferentiation. Cell 2018;173:338–54.

- Miao Z-F , Lewis MA , Cho CJ , Adkins-Threats M , Park D , Brown JW et al . A dedicated evolutionarily conserved molecular network licenses differentiated cells to return to the cell cycle. Dev Cell 2020;55:178–94.

- De Blander H , Morel A-P , Senaratne AP , Ouzounova M , Puisieux A . Cellular plasticity: a route to senescence exit and tumorigenesis. Cancers 2021;13:4561.

- Merrell AJ , Stanger BZ . Adult cell plasticity in vivo: de-differentiation and transdifferentiation are back in style. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016;17:413–25.

- Baylin SB , Jones PA . Epigenetic determinants of cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2016;8:a019505.

- Flavahan WA , Gaskell E , Bernstein BE . Epigenetic plasticity and the hallmarks of cancer. Science 2017;357:eaal2380.

- Jones PA , Issa J-PJ , Baylin S . Targeting the cancer epigenome for therapy. Nat Rev Genet 2016;17:630–41.

- Huang S . Tumor progression: Chance and necessity in Darwinian and Lamarckian somatic (mutationless) evolution. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2012;110:69–86.

- Darwiche N . Epigenetic mechanisms and the hallmarks of cancer: an intimate affair. Am J Cancer Res 2020;10:1954–78.

- Feng Y , Liu X , Pauklin S . 3D chromatin architecture and epigenetic regulation in cancer stem cells. Protein Cell 2021;12:440–54.

- Nam AS , Chaligne R , Landau DA . Integrating genetic and non-genetic determinants of cancer evolution by single-cell multi-omics. Nat Rev Genet 2021;22:3–18.

- Bitman-Lotan E , Orian A . Nuclear organization and regulation of the differentiated state. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS 2021;78:3141–58.

- Goldberg AD , Allis CD , Bernstein E . Epigenetics: a landscape takes shape. Cell 2007;128:635–8.

- Zeng Y , Chen T . DNA methylation reprogramming during mammalian development. Genes 2019;10:257.

- Hegde AN , Smith SG . Recent developments in transcriptional and translational regulation underlying long-term synaptic plasticity and memory. Learn Mem 2019;26:307–17.

- Kim S , Kaang B-K . Epigenetic regulation and chromatin remodeling in learning and memory. Exp Mol Med 2017;49:e281.

- Thienpont B , Van Dyck L , Lambrechts D . Tumors smother their epigenome. Mol Cell Oncol 2016;3:e1240549.

- Gameiro PA , Struhl K . Nutrient deprivation elicits a transcriptional and translational inflammatory response coupled to decreased protein synthesis. Cell Rep 2018;24:1415–24.

- Lin GL , Monje M . Understanding the deadly silence of posterior fossa A ependymoma. Mol Cell 2020;78:999–1001.

- Michealraj KA , Kumar SA , Kim LJY , Cavalli FMG , Przelicki D , Wojcik JB et al . Metabolic regulation of the epigenome drives lethal infantile ependymoma. Cell 2020;181:1329–45.

- Bakir B , Chiarella AM , Pitarresi JR , Rustgi AK . EMT, MET, plasticity, and tumor metastasis. Trends Cell Biol 2020;30:764–76.

- Gupta PB , Pastushenko I , Skibinski A , Blanpain C , Kuperwasser C . Phenotypic plasticity: driver of cancer initiation, progression, and therapy resistance. Cell Stem Cell 2019;24:65–78.

- Lambert AW , Weinberg RA . Linking EMT programmes to normal and neoplastic epithelial stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2021;21:325–38.

- Lindner P , Paul S , Eckstein M , Hampel C , Muenzner JK , Erlenbach-Wuensch K et al . EMT transcription factor ZEB1 alters the epigenetic landscape of colorectal cancer cells. Cell Death Dis 2020;11:147.

- Javaid S , Zhang J , Anderssen E , Black JC , Wittner BS , Tajima K et al . Dynamic chromatin modification sustains epithelial-mesenchymal transition following inducible expression of Snail-1. Cell Rep 2013;5:1679–89.

- Serrano-Gomez SJ , Maziveyi M , Alahari SK . Regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition through epigenetic and post-translational modifications. Mol Cancer 2016;15:18.

- Skrypek N , Goossens S , De Smedt E , Vandamme N , Berx G . Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition: epigenetic reprogramming driving cellular plasticity. Trends Genet TIG 2017;33:943–59.

- Li L , Hanahan D . Hijacking the neuronal NMDAR signaling circuit to promote tumor growth and invasion. Cell 2013;153:86–100.

- Li L , Zeng Q , Bhutkar A , Galván JA , Karamitopoulou E , Noordermeer D et al . GKAP acts as a genetic modulator of NMDAR signaling to govern invasive tumor growth. Cancer Cell 2018;33:736–51.

- Mohammadi H , Sahai E . Mechanisms and impact of altered tumour mechanics. Nat Cell Biol 2018;20:766–74.

- Odenthal J , Takes R , Friedl P . Plasticity of tumor cell invasion: governance by growth factors and cytokines. Carcinogenesis 2016;37:1117–28.

- Torres CM , Biran A , Burney MJ , Patel H , Henser-Brownhill T , Cohen A-HS et al . The linker histone H1.0 generates epigenetic and functional intratumor heterogeneity. Science 2016;353:aaf1644.

- Puram SV , Tirosh I , Parikh AS , Patel AP , Yizhak K , Gillespie S et al . Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of primary and metastatic tumor ecosystems in head and neck cancer. Cell 2017;171:1611–24.