The United Kingdom has developed rules for research using human embryo models for the first time. Scientists say they are pleased the country has clarified its position on this fast-moving area.

The voluntary code of conduct today published prohibits researchers from implanting embryo models made from human stem cells into the uterus of a living human or other animal. However, it does not set hard time limits on how long models can be grown in the lab, as some other countries have suggested. Instead, the code requires that projects propose their own limits based on the minimum time required to achieve their scientific goals, and that a monitoring committee be established to review and approve projects.

Human embryo research is subject to strict rules in most countries, including the UK, but until now there have been no specific rules in the UK governing research using laboratory-grown embryo models. The new code, developed by the University of Cambridge, London-based charity Progress Educational Trust (PET) and a team of researchers, closes a regulatory gap and addresses ethical concerns raised by advances in the field.

“The UK has a history of quickly setting up national rules on human embryo research and reproductive medicine, often through public consultation,” says Misao Fujita, a bioethicist at Kyoto University in Japan. “The world is closely following developments in the UK.”

Fast-paced research

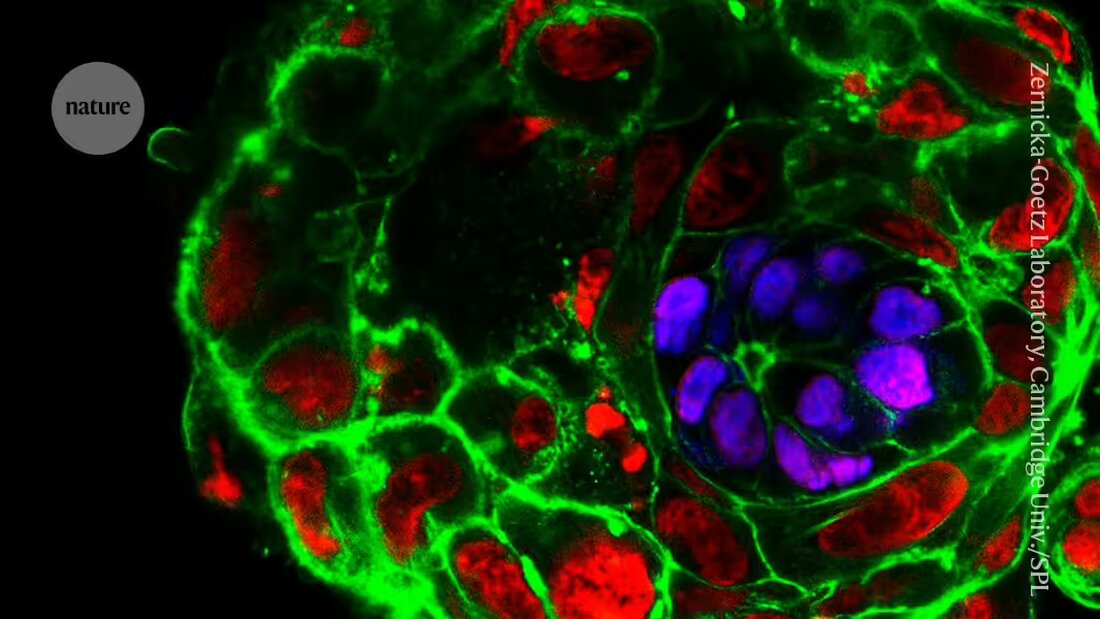

The research on Embryo models based on stem cells has exploded in the last five years. The models reconstruct various aspects of early embryonic development and could provide insights into infertility and pregnancy loss. They are attractive to researchers because they are not subject to the same legal and ethical restrictions as real human embryos and can be grown in large batches.

But with increasing Advanced of the models also have their own ethical questions that many countries are dealing with.

The British code helps researchers "move forward with a clear understanding of the process within their jurisdiction," says stem cell and developmental biologist Amander Clark, president of the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) in Evanston, Illinois. Last month, the ISSCR announced that it had established an Embryo Models Working Group, co-chaired by Clark, with recommendations for updating the ISSCR Guidelines will do.

Community response

Although the UK code is not legally binding, Sandy Starr, deputy director of the PET, said in a press conference that he was "confident" that it would be widely adopted by the research community, including funders, publishers and regulators. Therefore, he expected that “those who do not comply would find it impossible or difficult to publish in a reputable journal, obtain funding for their research, and also face censure from their colleagues.”

In developing the guidelines, the team sent an early draft for review to more than 50 researchers from around the world, including Israel, Japan and Australia. Jacob Hanna, a stem cell biologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, who was among those who reviewed an early draft, says the code integrates their comments well and its inclusive approach gives it greater relevance globally. “The guidelines and recommendations are sensible, careful and with an eye to the future,” he adds.

Supervisory Committee

The Code recommends that the Monitoring Committee review proposals for research using stem cell-based embryo models and that all proposals be recorded in a registry. Projects should be approved if they adhere to a number of research principles, including consideration of a well-founded scientific objective, obtaining appropriate consent from source cell donors, and clarifying research benefits.

The code, which is regularly updated, also requires researchers to specify how their models are terminated, using methods such as quick-freezing or chemical fixation to destroy the cells' functions.

Bioethicist Søren Holm of the University of Manchester, UK, who also works in Oslo, says the monitoring committee's wide discretion could create suspicion that it is prioritizing scientific promises over ethical concerns - in other words, people could fear that "it is not regulating science, just legitimizing it". Because he does not commit to hard limits on culture time or the appearance of problematic features such as embryo models with advanced stages of neuronal development, "many people will find the code weak," he says. If members of the committee are for some reason perceived to be biased or lack the necessary expertise, that could "present an obstacle" to adopting the code, Holm says.

Developmental biologist Nicolas Rivron of the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna, who also reviewed an early draft of the code, agrees that setting a time limit for models makes sense to "give the public reassurance that research is not proceeding unchecked." Agencies in France and the Netherlands have suggested that certain types of embryo models should not be cultured beyond the equivalent of 28 days after fertilization.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto