Bile reflux

Bile reflux

overview

Bile reflux

Bile reflux

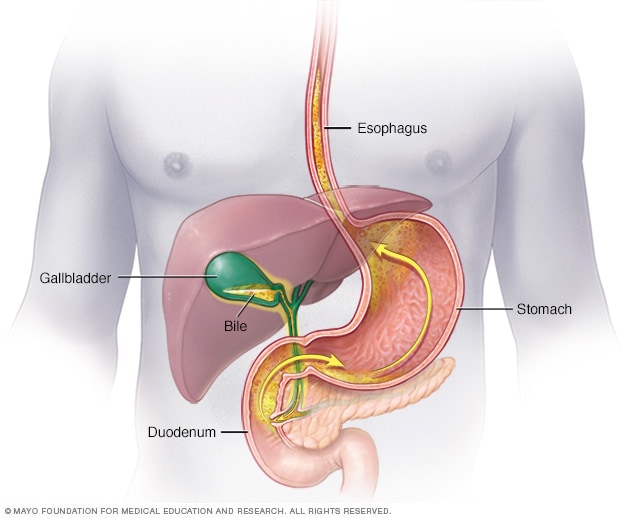

Bile is a digestive fluid produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder. During bile reflux, digestive fluid flows back into the stomach and, in some cases, the esophagus.

Bile reflux occurs when bile—a digestive fluid produced in your liver—backflows (reflux) into your stomach and, in some cases, into the tube that connects your mouth and stomach (esophagus).

Bile reflux can accompany the reflux of stomach acid (stomach acid) into your esophagus. Gastric reflux can lead to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), a potentially serious problem that causes irritation and inflammation of the esophageal tissue.

Unlike stomach acid reflux, bile reflux cannot be completely controlled through diet or lifestyle changes. Treatment includes medication or, in severe cases, surgery.

Symptoms

Bile reflux can be difficult to distinguish from stomach acid reflux. The signs and symptoms are similar and the two conditions can occur at the same time.

Signs and symptoms of bile reflux include:

- Schmerzen im Oberbauch, die schwerwiegend sein können

- Häufiges Sodbrennen – ein brennendes Gefühl in der Brust, das sich manchmal bis in den Hals ausbreitet, zusammen mit einem sauren Geschmack im Mund

- Brechreiz

- Erbrechen einer grünlich-gelben Flüssigkeit (Galle)

- Gelegentlich Husten oder Heiserkeit

- Unbeabsichtigter Gewichtsverlust

When to go to the doctor?

Make an appointment with your doctor if you have frequent reflux symptoms or if you are losing weight without trying.

If you have been diagnosed with GERD but your medications are not providing adequate relief, contact your doctor. You may need additional treatment for bile reflux.

Causes

Bile is important for digesting fats and removing worn-out red blood cells and certain toxins from your body. Bile is produced in your liver and stored in your gallbladder.

Eating a meal that contains even a small amount of fat signals your gallbladder to release bile, which flows through a small tube to the upper part of your small intestine (duodenum).

Bile reflux into the stomach

Bile and food mix in the duodenum and enter your small intestine. The pyloric valve, a heavy ring of muscle at the exit of the stomach, normally opens only slightly—enough to release about an eighth of an ounce (about 3.75 milliliters) or less of liquefied food at a time, but not enough to allow digestive juices to flow back into the stomach.

When bile reflux occurs, the valve does not close properly and the bile is flushed back into the stomach. This can lead to inflammation of the stomach lining (reflux gastritis).

Bile backflow into the esophagus

Bile and stomach acid can flow back into the esophagus if another muscle valve, the lower esophageal sphincter, is not functioning properly. The lower esophageal sphincter separates the esophagus and stomach. The valve usually opens just long enough to allow food to pass into the stomach. But if the valve weakens or relaxes abnormally, bile can be flushed back into the esophagus.

What causes bile reflux?

Bile reflux can be caused by:

- Operationskomplikationen. Magenoperationen, einschließlich der vollständigen oder teilweisen Entfernung des Magens und Magenbypassoperationen zur Gewichtsreduktion, sind für die meisten Gallenrückflüsse verantwortlich.

- Peptische Geschwüre. Ein Magengeschwür kann die Pylorusklappe blockieren, sodass sie sich nicht richtig öffnet oder schließt. Stehende Nahrung im Magen kann zu erhöhtem Magendruck führen und Galle und Magensäure in die Speiseröhre zurückfließen lassen.

- Gallenblase Chirurgie. Menschen, denen die Gallenblase entfernt wurde, haben deutlich mehr Gallenrückfluss als Menschen, die diese Operation nicht hatten.

Complications

Bile reflux gastritis has been linked to stomach cancer. The combination of bile reflux and acid reflux also increases the risk of the following complications:

-

Gerd.This condition, which causes irritation and inflammation of the esophagus, is most often due to excess acid, but bile can mix with the acid.

Bile is often suspected of contributing to GERD when people respond incompletely or not at all to strong acid-suppressing medications.

- Barrett-Ösophagus. Dieser schwerwiegende Zustand kann auftreten, wenn eine langfristige Exposition gegenüber Magensäure oder Säure und Galle das Gewebe in der unteren Speiseröhre schädigt. Die geschädigten Ösophaguszellen haben ein erhöhtes Krebsrisiko. Tierstudien haben auch den Gallenrückfluss mit dem Barrett-Ösophagus in Verbindung gebracht.

- Speiseröhrenkrebs. Es gibt einen Zusammenhang zwischen saurem Reflux und Galle-Reflux und Speiseröhrenkrebs, der möglicherweise erst diagnostiziert wird, wenn er ziemlich weit fortgeschritten ist. In Tierversuchen hat sich gezeigt, dass Gallenrückfluss allein Speiseröhrenkrebs verursacht.

Sources:

- Townsend CM Jr., et al. Magen. In: Sabiston Lehrbuch der Chirurgie: Die biologische Grundlage der modernen chirurgischen Praxis. 20. Aufl. Elsevier; 2017. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Abgerufen am 15. Januar 2020.

- Brunicardi FC, et al., Hrsg. Magen. In: Schwartz‘ Prinzipien der Chirurgie. 11. Aufl. McGraw-Hill; 2019. https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com. Abgerufen am 16. Januar 2020.

- Saurer Reflux (GER & GERD) bei Erwachsenen. Nationales Institut für Diabetes und Verdauungs- und Nierenerkrankungen. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/acid-reflux-ger-gerd-adults/all-content. Abgerufen am 15. Januar 2020.

- Rakel D, Hrsg. Gastroösophageale Refluxkrankheit. In: Integrative Medizin. 4. Aufl. Elsevier; 2018. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Abgerufen am 15. Januar 2020.

- Hammer GD, et al., Hrsg. Magen-Darm-Erkrankung. In: Pathophysiologie der Krankheit: Eine Einführung in die klinische Medizin. 8. Aufl. McGraw-Hill; 2019. https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com. Abgerufen am 16. Januar 2020.

- McCabe ME, et al. Neue Ursachen für das alte Problem der Galle-Reflux-Gastritis. Klinische Gastroenterologie und Hepatologie. 2018; doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.02.034.

- Caspa Gokulan R, et al. Von der Genetik zu Signalwegen: Molekulare Pathogenese des Ösophagus-Adenokarzinoms. Biochimica und Biophysica Acta. Rezensionen zu Krebs. 2019; doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2019.05.003.

- Khanna S., Hrsg. Erkrankung der Gallenblase. In: Mayo-Klinik für Verdauungsgesundheit. 4. Aufl. Mayo Clinic Press; 2020.

- Halle JE. Antrieb und Durchmischung von Nahrung im Verdauungstrakt. In: Guyton und Hall Lehrbuch der Medizinischen Physiologie. 13. Auflage. Elsevier; 2016. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Abgerufen am 20. Januar 2020.

- Guirat A. et al. Eine Anastomose Magenbypass und Krebsrisiko. Adipositas-Chirurgie. 2018; doi:10.1007/s11695-018-3156-5.

- Fass R. Ansatz zur refraktären gastroösophagealen Refluxkrankheit bei Erwachsenen. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Abgerufen am 20. Januar 2020.

- Ambulante pH-Überwachung. Merck Manual Professional-Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/gastrointestinal-disorders/diagnostic-and-therapeutic-gastrointestinal-procedures/ambulatory-ph-monitoring. Abgerufen am 21. Januar 2020.

- Rajan E (Gutachten). Mayo-Klinik. 20. März 2020.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto