Testicular cancer

Testicular cancer

overview

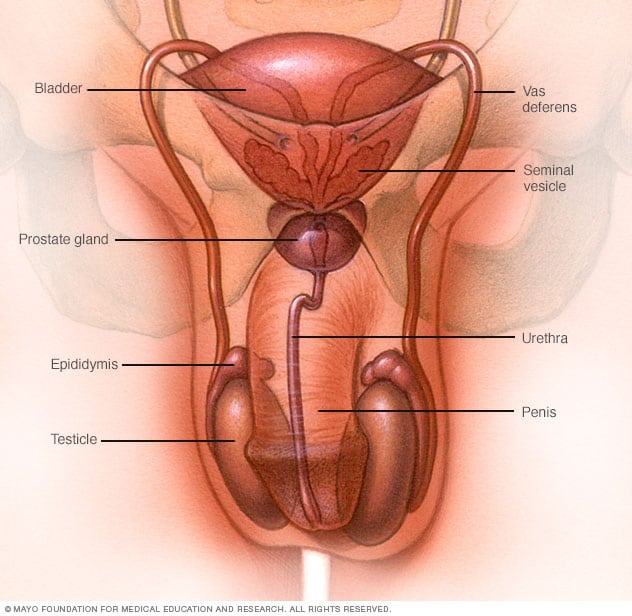

Male reproductive system

Male reproductive system

The male reproductive system produces, stores and moves sperm. Testicles produce sperm. Fluid from the seminal vesicles and prostate gland combines with sperm to form semen. The penis ejaculates semen during sexual intercourse.

Testicular cancer occurs in the testicles (testicles), which are located in the scrotum, a loose bag of skin under the penis. The testicles produce male sex hormones and sperm for reproduction.

Compared to other types of cancer, testicular cancer is rare. But testicular cancer is the most common cancer in American men between the ages of 15 and 35.

Testicular cancer is treatable, even if the cancer has spread beyond the testicle. Depending on the type and stage of testicular cancer, you may receive one of several treatments or a combination.

Symptoms

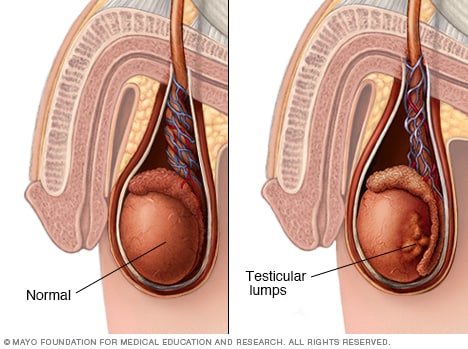

Testicular lumps

Testicular lumps

Pain, swelling, or lumps in your testicle or groin area may be a sign or symptom of testicular cancer or other conditions that require treatment.

Signs and symptoms of testicular cancer include:

- Ein Knoten oder eine Vergrößerung in einem der Hoden

- Schweregefühl im Hodensack

- Ein dumpfer Schmerz im Unterleib oder in der Leistengegend

- Eine plötzliche Ansammlung von Flüssigkeit im Hodensack

- Schmerzen oder Beschwerden in einem Hoden oder Hodensack

- Vergrößerung oder Zärtlichkeit der Brüste

- Rückenschmerzen

Cancer usually affects only one testicle.

When to go to the doctor?

See your doctor if you notice pain, swelling, or lumps in your testicles or groin, especially if these signs and symptoms persist for more than two weeks.

Causes

It's not clear what causes testicular cancer in most cases.

Doctors know that testicular cancer occurs when healthy cells in a testicle become altered. Healthy cells grow and divide in an orderly manner so your body functions normally. But sometimes some cells develop abnormalities that cause this growth to get out of control - these cancer cells continue to divide even when new cells are not needed. The accumulating cells form a mass in the testicle.

Almost all testicular cancers begin in the germ cells – the cells in the testicles that produce immature sperm. What causes germ cells to become abnormal and develop into cancer is not known.

Risk factors

Factors that may increase your risk of testicular cancer include:

-

An undescended testicle (cryptorchidism).The testicles form in the abdominal area during fetal development and normally descend into the scrotum before birth. Men who have a testicle that never descended have a higher risk of testicular cancer than men whose testicles descended normally. The risk remains increased even if the testicle has been surgically relocated into the scrotum.

Still, the majority of men who develop testicular cancer have no history of undescended testicles.

- Abnorme Hodenentwicklung. Bedingungen, die zu einer abnormalen Entwicklung der Hoden führen, wie das Klinefelter-Syndrom, können Ihr Risiko für Hodenkrebs erhöhen.

- Familiengeschichte. Wenn Familienmitglieder Hodenkrebs hatten, besteht möglicherweise ein erhöhtes Risiko.

- Das Alter. Hodenkrebs betrifft Teenager und jüngere Männer, insbesondere solche zwischen 15 und 35 Jahren. Er kann jedoch in jedem Alter auftreten.

- Wettrennen. Hodenkrebs ist bei weißen Männern häufiger als bei schwarzen Männern.

prevention

There is no way to prevent testicular cancer.

Some doctors recommend regular testicular self-exams to detect testicular cancer at its earliest stages. But not all doctors agree. Discuss testicular self-examination with your doctor if you are unsure whether it is right for you.

Treatment of testicular cancer

Sources:

- Niederhuber JE, et al., Hrsg. Hodenkrebs. In: Abeloffs Klinische Onkologie. 5. Aufl. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2014. http://www.clinicalkey.com. Abgerufen am 29. November 2016.

- Hodenkrebs. Fort Washington, Pa.: Nationales umfassendes Krebsnetzwerk. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. Abgerufen am 14. Dezember 2016.

- Wein AJ, et al., Hrsg. Neubildungen der Hoden. In: Campbell-Walsh-Urologie. 11. Aufl. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevier; 2016. http://www.clinicalkey.com. Abgerufen am 29. November 2016.

- Hodenselbstuntersuchung (TSE). Urologische Pflegestiftung. http://www.urologyhealth.org/urology/index.cfm?article=101. Abgerufen am 12. Dezember 2016.

- Ilic D, et al. Screening auf Hodenkrebs. Cochrane-Datenbank systematischer Reviews. 2011;CD007853. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD007853.pub2/abstract. Abgerufen am 16. Dezember 2016.

- Riggin EA. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, Oktober 2016.

- Cheney SM, et al. Roboterassistierte retroperitoneale Lymphknotendissektion: Technik und erste Fallserie von 18 Patienten. BJU International. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bju.12804/full. Abgerufen am 16. Dezember 2016.

- Costello BA (Gutachten). Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, 29. Januar 2017.

- Steele SS, et al. Klinische Manifestationen, Diagnose und Staging von testikulären Keimzelltumoren. http://www.uptodate.com/home. Abgerufen am 29. November 2016.

- Anastasiou I, et al. Synchrone bilaterale Hodentumoren mit unterschiedlicher Histopathologie. Fallberichte in der Urologie. 2015;492183:1.

- Rovito MJ, et al. Von „D“ zu „I“: Eine Kritik der aktuellen Empfehlung der United States Preventive Services Task Force zur Hodenkrebsvorsorge. Berichte zur Präventivmedizin. 2016;3:361.

- Amin MB, et al., Hrsg. Hoden. In: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8. Aufl. New York, NY: Springer; 2017.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto