Exposure to third-hand smoke increases biomarkers associated with the development of skin diseases

Third Hand Smoke (THS) includes the residual tobacco smoke pollutants that remain on surfaces and in dust after smoking tobacco. It can remain on indoor surfaces indefinitely, posing a potentially harmful exposure to both smokers and non-smokers. A team led by researchers at the University of California, Riverside has found that acute skin exposure to DBS increases biomarkers associated with the development of skin diseases such as contact dermatitis and psoriasis. “We found that exposure to DBS on human skin triggers mechanisms of inflammatory skin diseases and the biomarkers...

Exposure to third-hand smoke increases biomarkers associated with the development of skin diseases

Third Hand Smoke (THS) includes the residual tobacco smoke pollutants that remain on surfaces and in dust after smoking tobacco. It can remain on indoor surfaces indefinitely, posing a potentially harmful exposure to both smokers and non-smokers.

A team led by researchers at the University of California, Riverside has found that acute skin exposure to DBS increases biomarkers associated with the development of skin diseases such as contact dermatitis and psoriasis.

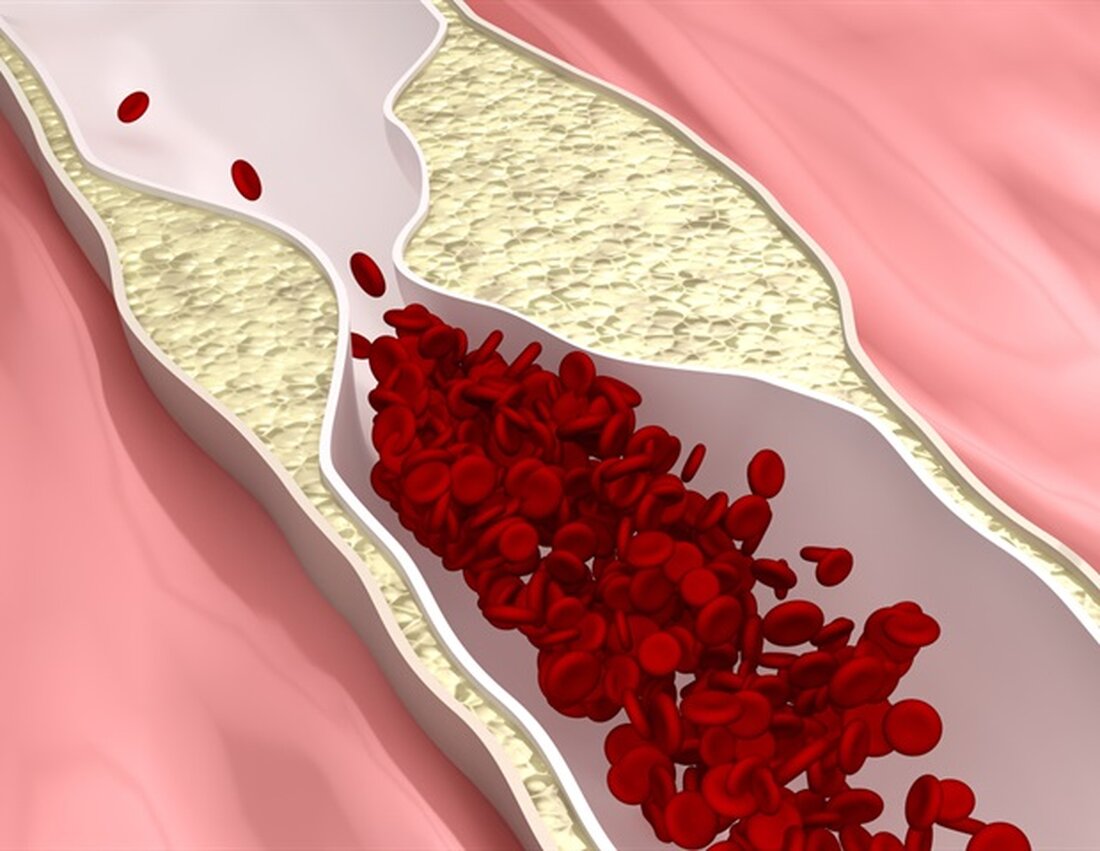

“We found that exposure of human skin to DBS triggers mechanisms of inflammatory skin diseases and increases oxidative damage biomarkers in urine, which could lead to other diseases such as cancer, heart disease and atherosclerosis,” said Shane Sakamaki-Ching, a former graduate student at UC Riverside who completed his doctorate in cell, molecular and developmental biology in March 2022. “Alarmingly, acute dermal exposure to DBS mimics the harmful effects of cigarette smoking.”

The study, published in eBioMedicine of The Lancet family of journals, is the first to be conducted on people dermally exposed to DBS.

Ten healthy non-smokers aged 22 to 45 years took part in the clinical study, which took place at UC San Francisco. For three hours, each participant wore DBS-impregnated clothing and walked or ran on a treadmill for at least 15 minutes every hour to stimulate sweating and increase skin absorption of DBS. Participants did not know that the clothing contained THS. Blood and urine samples were then collected from participants at regular intervals to identify protein changes and markers of oxidative stress caused by DBS. Participants in the control exposure wore clean clothing.

“We found that acute DBS exposure caused an increase in urinary biomarkers of oxidative damage to DNA, lipids and proteins, and these biomarkers remained high after exposure stopped,” said Sakamaki-Ching, now a research scientist at Kite Pharma in California, where he leads a stem cell team. "Cigarette smokers show the same increase in these biomarkers. Our findings can help physicians diagnose patients exposed to DBS and help develop regulatory guidelines for remediation of indoor environments contaminated with DBS."

Prue Talbot, a professor of cell biology in whose lab Sakamaki-Ching worked, explained that the skin is the largest organ that comes into contact with DBS and therefore may be the most exposed.

"There is a general lack of knowledge about human health responses to THS exposure," said Talbot, the paper's corresponding author. "If you buy a used car that used to belong to a smoker, you are exposing yourself to some health risk. If you go to a casino where smoking is allowed, you are exposing your skin to THS. The same goes for staying in a hotel room." was previously occupied by a smoker.”

The DBS exposures to which the 10 participants were exposed were relatively short and did not cause any visible changes in the skin. Nevertheless, molecular biomarkers in the blood associated with the activation of early-stage contact dermatitis, psoriasis and other skin diseases were increased.

This supports the idea that dermal exposure to DBS could lead to the molecular triggering of inflammatory skin diseases.”

Shane Sakamaki-Ching, former graduate student at UC Riverside

Next, the researchers want to examine the residues from electronic cigarettes that can come into contact with human skin. They also plan to study larger populations exposed to dermal DBS for longer periods of time.

Sakamaki-Ching and Talbot were joined in the study by Jun Li of UCR, Suzaynn Schick of UC San Francisco, and Gabriela Grigorean of UC Davis.

The study was supported by grants to Talbot and Schick from the Tobacco Related Disease Research Program of California.

Source:

University of California – Riverside

Reference:

Sakamaki-Ching, S., et al. (2022) Dermal third-hand smoke exposure results in oxidative damage, triggers skin inflammatory markers, and adversely alters the human plasma proteome. eBioMedicine. doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104256.

.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto